Black Power/White Backlash

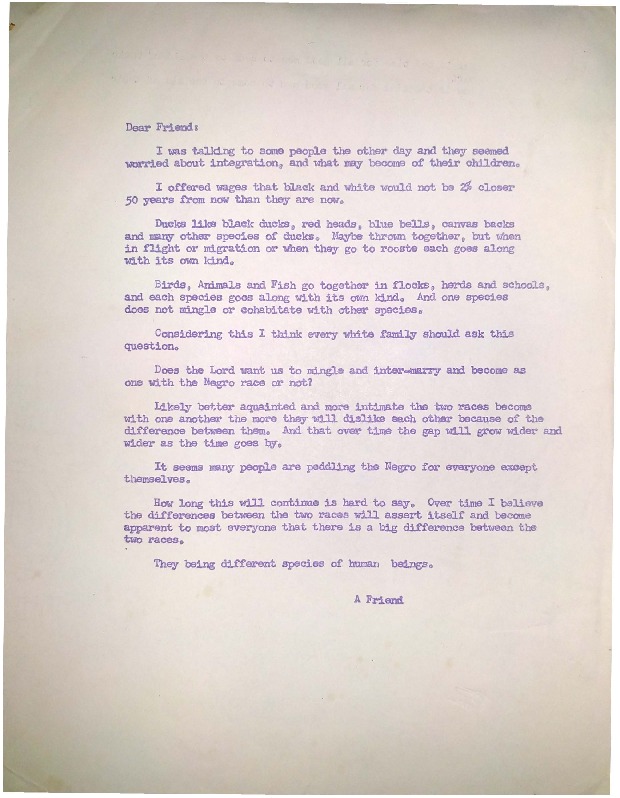

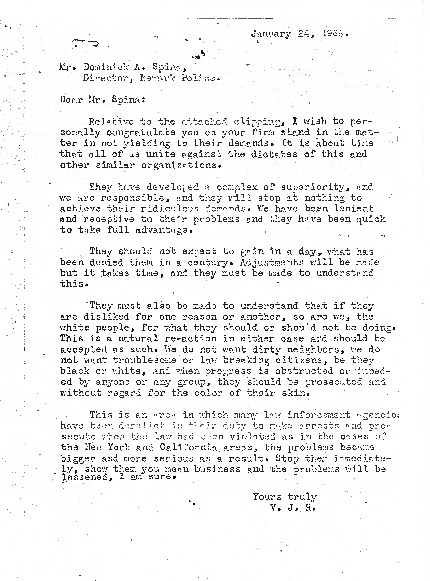

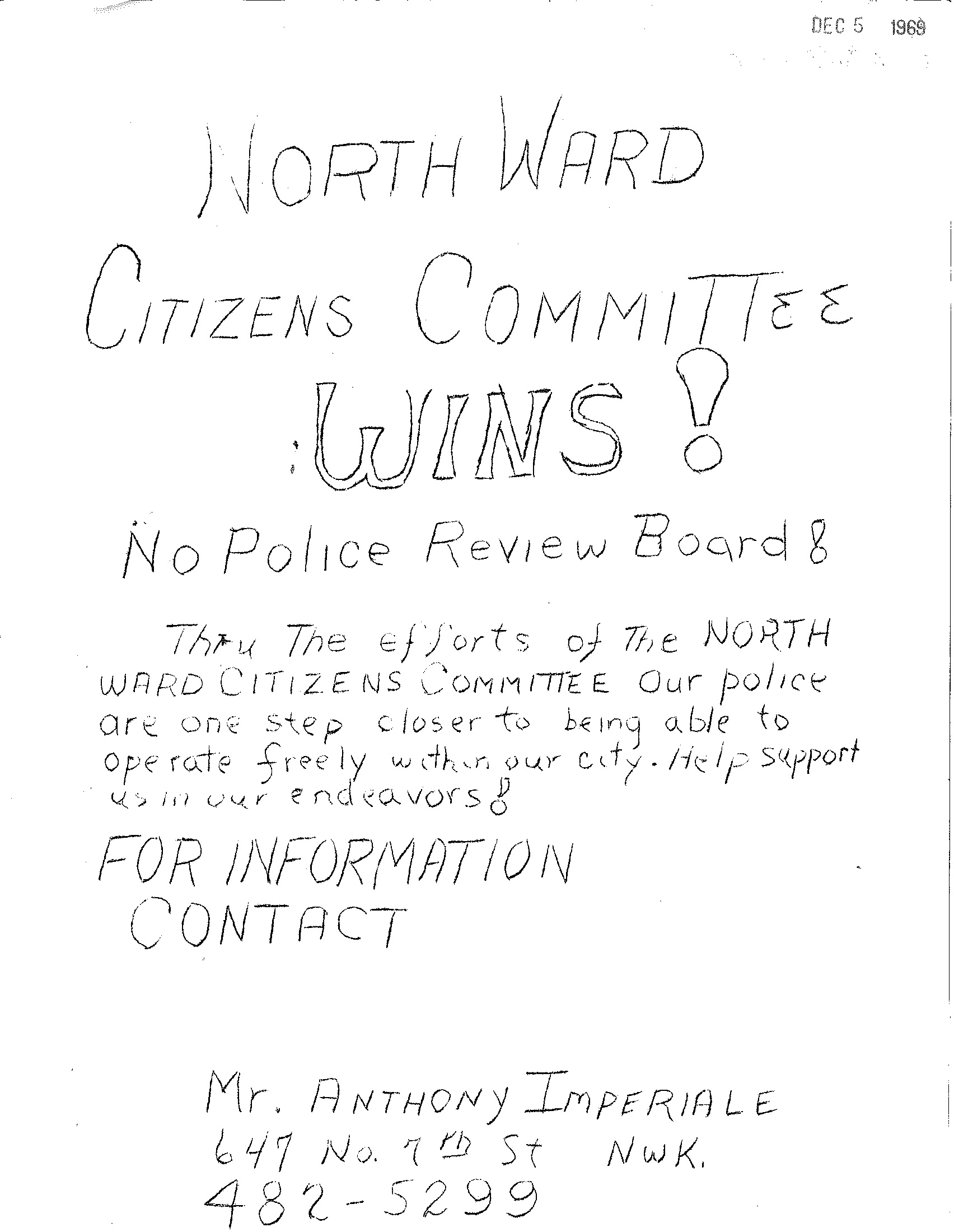

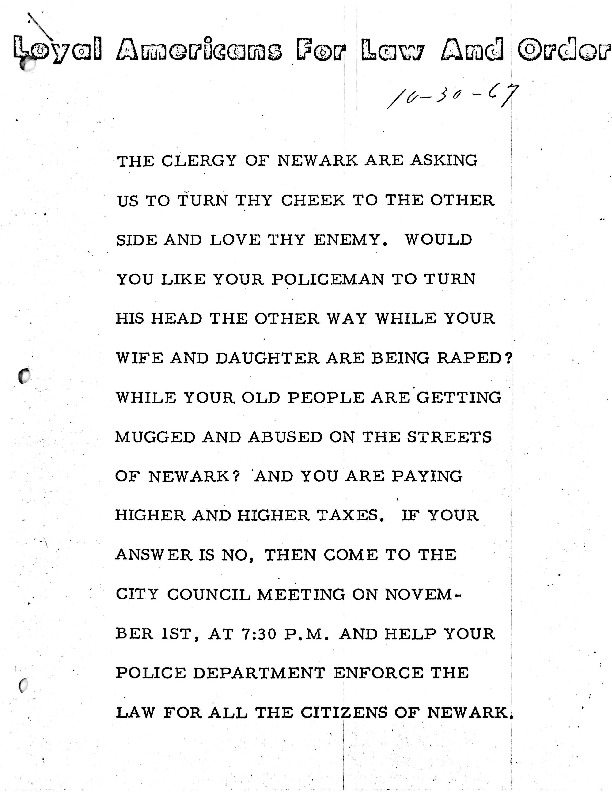

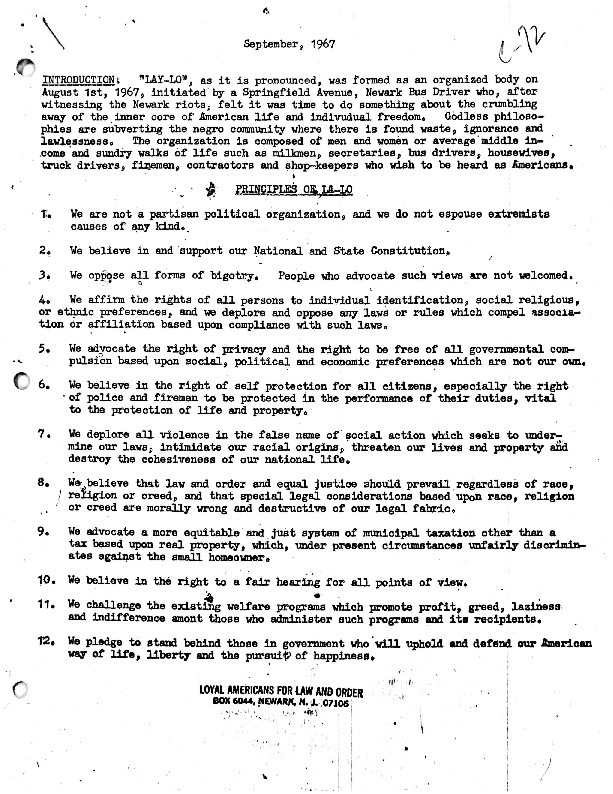

When the rebellion was over and order was restored to the streets of Newark, some whites feared for their lives. Those able to leave fled to the suburbs. But some stayed, for whatever reasons, particularly the Italians in the North Ward. A white vigilante, by the name of Anthony Imperiale, formed the North Ward Citizens Committee, famously stating, “If the black panther comes, the white hunter will be waiting.” For many years, Bloomfield Avenue in Newark, a major county road running from west from Newark to Montclair and beyond, was as far north as African Americans could venture. To cross over was indeed very dangerous, similar to the boundaries between white and black neighborhoods in the South under Jim Crow.

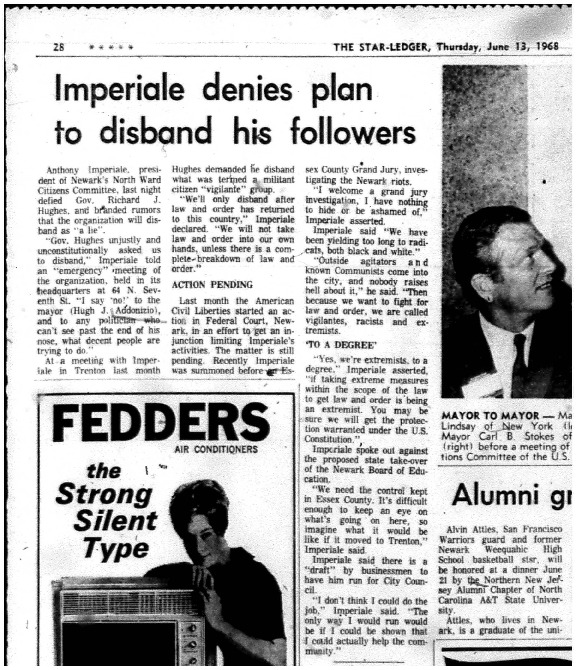

Imperiale was more interested in expanding his personal power and influence than waiting for blacks to enter “his” territory. In 1968, during the Model Cites Citizens Council election, Imperiale won a seat on the newly created council. At the Council’s first meeting, somebody nominated him for one of the two vice-president seats, on a Council dominated by a solid black majority, and he won. It was no joking matter to the United Brothers and the Committee for Unified Newark (CFUN). A plan was hatched to remove him from office at the next meeting. The plan went awry when two individuals who were to make and second the recall motion failed to show up at the meeting. The confrontation almost turned violent, with Baraka’s Black Community Development and Defense (BCD) surrounding Imperiale’s North Ward Citizens Committee fighters. Members of the BCD watched from roof tops around the Model Cities office, waiting for the order to strike. Cooler heads prevailed, thus avoiding an all out race war. But the damage had been done.

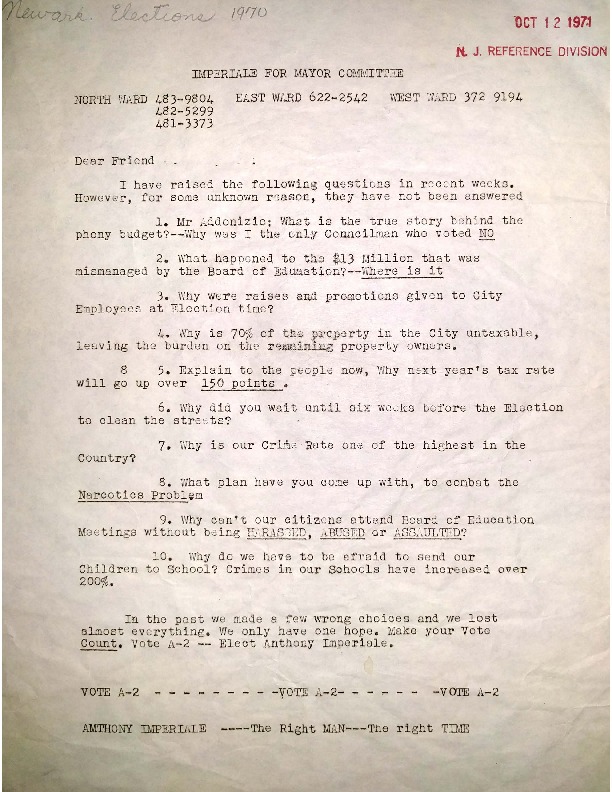

Imperiale never came back to a meeting of the Neighborhood Council. But on the strength of his “victory” over black people on their own turf (since federal programs were deemed to be “black programs”), Imperiale parlayed his win into a seat for himself on the Newark City Council in a special election in 1968. There were 10,000 voters (mostly from the North Ward) who always carried his torch, enough for City Council, and later for a seat in the New Jersey Senate as an independent. These voters, however, were not enough for his campaign for Mayor in the race against Ken Gibson in 1970, and again in 1974.

Eventually, as his Italian and Irish base finally left town for the suburbs or the Jersey Shore, Imperiale became less of an issue. But not before destroying Baraka’s dream of housing development in the North Ward with his stand in concert with Steve Adubato against the construction of Kawaida Towers in 1972.

Explore The Archives