The Black Organization of Students (BOS)

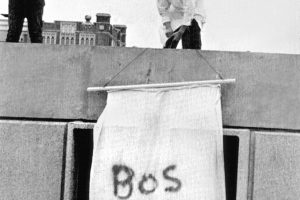

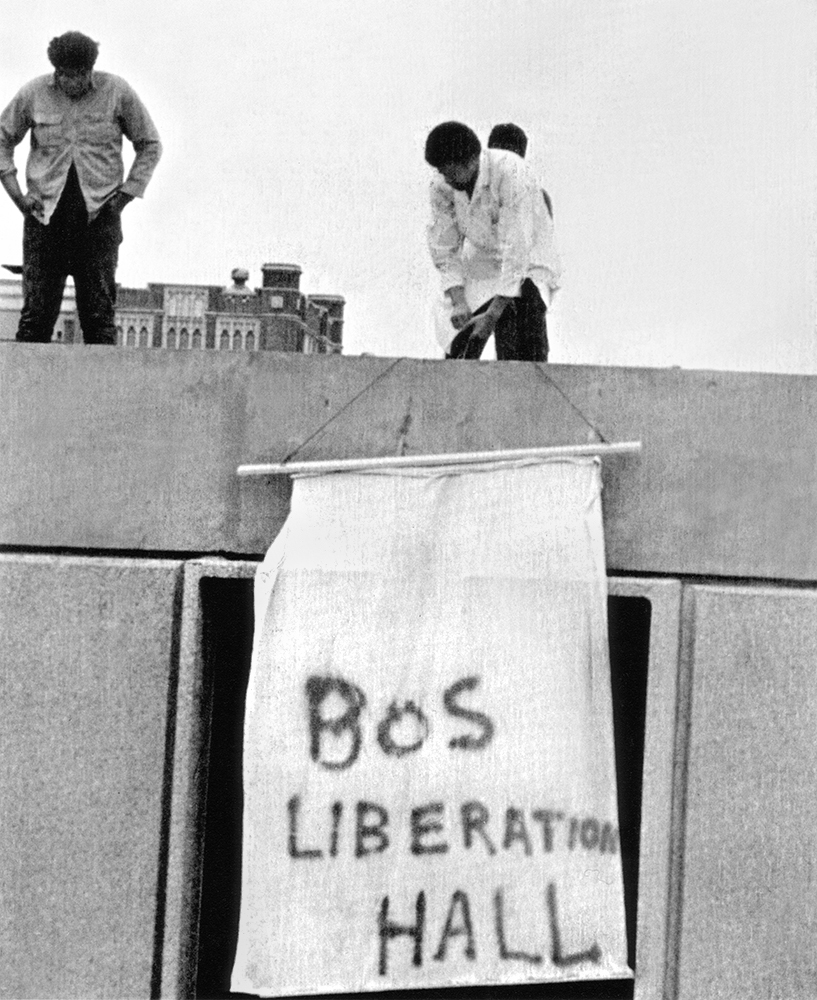

On February 24, 1969 at 6:30 AM, members of Black Organization of Students (BOS) marched into Conklin Hall, the main classroom building on campus, kicked out the security guard, and chained the doors closed. Equipped with food and water, the students announced that they would remain in Conklin hall until their demands were met by the University’s administration. Shortly after occupying the building, Marvin McGraw, Bill Kinchelow, and Howard Kinchelow unfurled a banner from the roof declaring the building “Liberation Hall.”

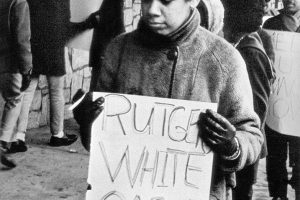

The black undergraduate students at Rutgers-Newark were mad because there were very few black faculty members and students on any of the three campuses in 1969, and mad at the way blacks were treated on the Rutgers campus. At the time, only 148 (or 4%) of the 3,300 undergraduate students enrolled at Rutgers-Newark were black, with no black faculty members on campus, while the black population in Newark had grown to over 60% of the city’s total population by 1969.

On February 13th, over a week before the “liberation” of Conklin Hall, BOS issued a statement of demands to Vice-President Malcolm Talbott. The demands included provisions for the recruitment and retention of black students and faculty, support for community programs, and the formation of a degree-granting Black Studies Institute. “We wanted to see a greater black presence on campus,” BOS member Joe Brown recalled. Additionally, BOS wanted “a broader presence of Rutgers in the Newark community in terms of affecting the educational situation within the city. And we thought that as an urban university, that Rutgers should address the needs of the urban community to some degree.”

Frustrated by the administration’s continued rejection of their demands, BOS decided that they needed to escalate their protests. “I remember people suggesting that we boycott classes…whether or not we would have marches and rallies,” BOS leader Vickie Donaldson recalled. “And I remember the more extreme of us saying if our demands are not met, the university ought to be unable to function, period.”

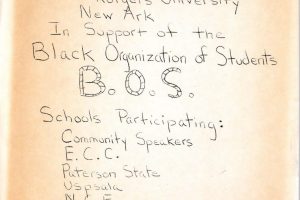

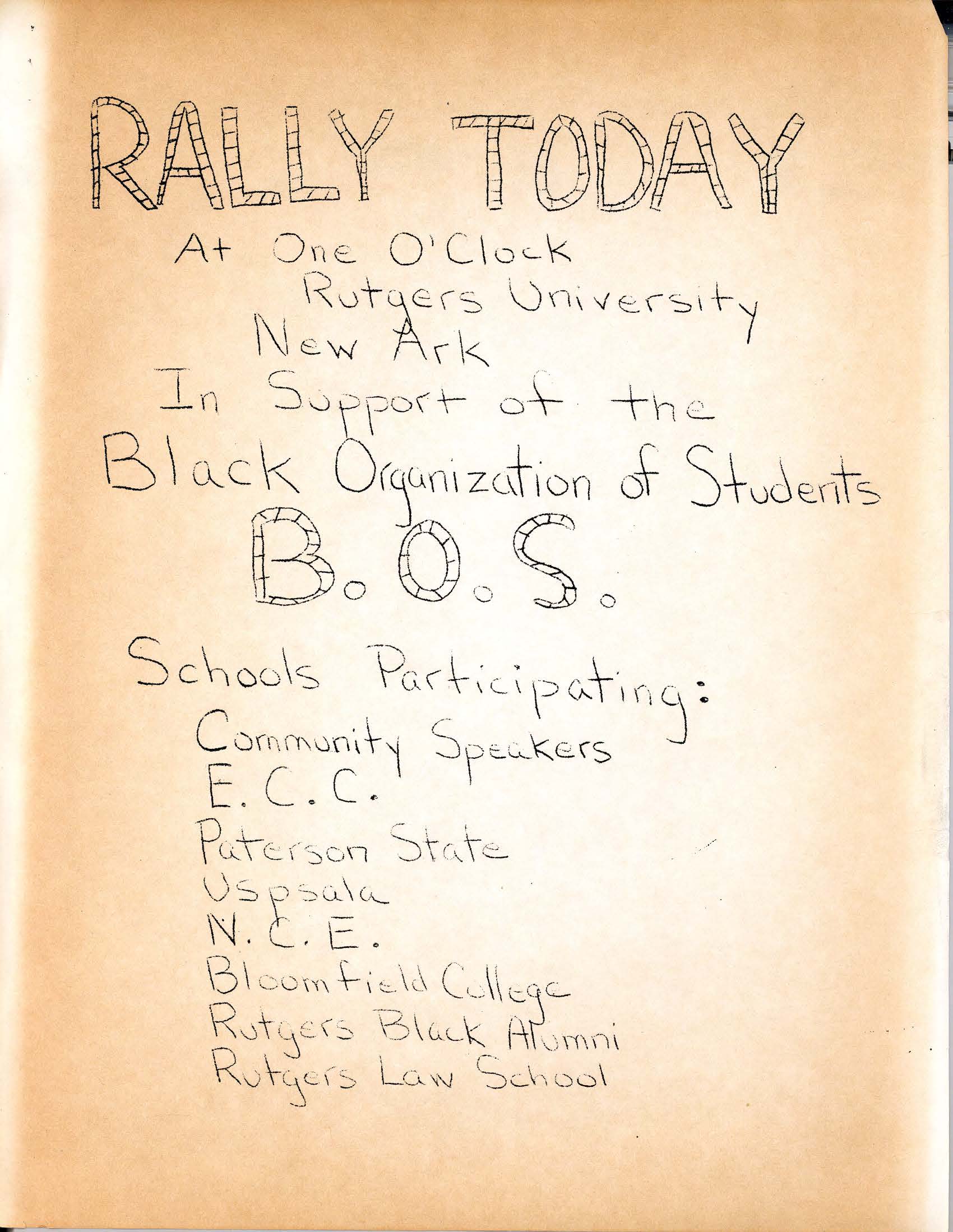

After holding all-night meetings and debates, when the decision was finally reached to takeover Conklin Hall, BOS members formulated a highly-regimented plan for occupying the building. Members acquired blueprints of the buildings and arranged for supplies to last throughout the occupation. BOS also reached out to civil rights and Black Power organizations in the Newark community to support their actions. “Joe Brown asked for our help,” Junius Williams, Director of the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA), later reflected. In addition to the BOS members outside Conklin, SDS and other progressive white students on campus, NAPA, the United Brothers, and other community organizations supported the students on the outside. “I remember sleeping overnight in Ackerson Hall, across the street in what was the Law School at that time,” reported Williams. “We conducted press conferences to ‘explain and warn.’ During our watch, some of the guys on our team had to take a battering ram away from local white vigilante Anthony Imperiale’s boys, who were planning to break down the door at Conklin to get the black students out. I was off campus, so to speak, on food procurement detail. When I returned, I found our young men flexing their muscles, proclaiming that “ain’t nothin’ comin’ through here! Such was the nature of the bond between Town and Gown: they supported us, we supported them.”

The 72-hour period of the BOS occupation of Liberation Hall was a tense scene, as supporters and adversaries gathered outside the building. In many ways, Rutgers-Newark became ground zero for the ongoing debates over education, affirmative action and Black Power in the late 1960s during those three days. “There was also discussion to end the protest by taking back the building . . . by force,” Newark historian and Rutgers Professor Clement Price recalled. “Gus Heningburg negotiated with Governor Richard Hughes to keep the New Jersey State Police—the Troopers—off the campus, certainly to keep them out of the building. Had he and others not been successful, I don’t think we would now celebrate the Liberation of Conklin Hall. Instead, we would likely commemorate it as a tragic event.”

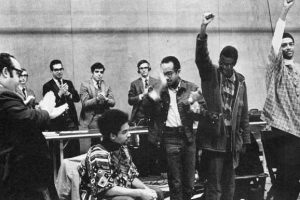

After the occupation of Conklin Hall ended, BOS entered into a lengthy series of negotiations with University administrators and state officials to implement their demands. On March 8th, BOS leaders held a news conference to announce that the university reneged on their initial agreement, and vowed that more protests would follow. The same day, however, the NJ State Board of Education “urged Rutgers and other state colleges to amend admission standards to enroll more minorities.”

The following week, at “an emotional 8 hour meeting”, on March 14th, the Rutgers Board of Governors voted to “establish a new and pioneering program to admit economically disadvantaged high school graduates in Newark, New Brunswick and Camden.” The Liberation of Conklin Hall had “fundamentally changed” Rutgers, Dr. Price said. “It set the stage for the creation of the EOF Program; it set the stage for an African American Studies Program that matured into a Department; it enabled the naming of the campus center in honor of Rutgers alumnus, Paul Robeson.”

At a program to commemorate the 40th Anniversary of the Conklin Hall takeover, then President Richard McCormick said, “Rutgers had not caused the fundamental racial and economic inequalities that characterized American life, but prior to that day neither had Rutgers done very much to address those inequalities. These young men and women wanted Rutgers to serve them and their communities, too, and they were right.”

As Dr. Price later wrote, “Perhaps more than anything during that period, the joining of forces and the joining of aspirations and ideals surrounding the Liberation of Conklin Hall, marked the beginning of Rutgers Newark’s future as the most diverse campus in the United States.”

References:

Joseph Brown, interview by Gilbert Cohen, Preserving Memory: Newark and Rutgers in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Rutgers University-Newark John Cotton Dana Library, October 18, 1991.

Vickie Donaldson, interview by Gilbert Cohen, Preserving Memory: Newark and Rutgers in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Rutgers University-Newark John Cotton Dana Library, November 12, 1991.

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power.

“40th Anniversary, 1969-2009: The 1969 Liberation of Conklin Hall” (Commemorative Journal), Rutgers University-Newark.

Marvin McGraw, Bill and Howard Kinchelow, members of the Black Organization of Students, unfurl a banner from Conklin Hall’s roof top renaming the building Liberation Hall. It was the first time a Rutgers building had ever been occupied by students. — Credit: John Cotton Dana Library, Rutgers-Newark

Compilation of raw video footage from NBC News on the “takeover” of Conklin Hall by members of the Black Organization of Students (BOS) at Rutgers University-Newark in February, 1969. — Credit: NBC Universal

Flyer for a rally at Rutgers University-Newark in support of the Black Organization of Students (BOS). Community leaders and organizations at other local colleges showed up at RU-N to support the BOS during the takeover of Conklin Hall in February, 1969. — Credit: John Cotton Dana Library, Rutgers University-Newark

Press release issued by the Rutgers News Service on March 3, 1969, describing the University’s responses to each of the demands of the Black Organization of Students (BOS). BOS members took over Conklin Hall on February 24th for three days, after the administration rejected their initial demands for greater recruitment of minority students and faculty. –Credit: John Cotton Dana Library, Rutgers University-Newark