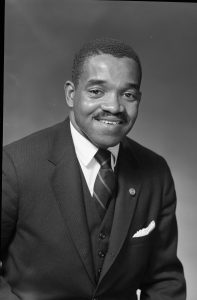

Calvin West

Calvin West was born November 13, 1932, in Newark and grew up in the city’s old Third Ward. He attended Newark public schools, first attending Charlton Street School before graduating from South Side High School (now Malcolm X Shabazz). West had a relatively comfortable upbringing, but he recalled his first experience with racism took place while he was playing in a basketball game at South Side. After he accidentally stepped on the shoe of a white spectator during the game, West was accosted by five white men outside the locker room who called him racial slurs. One of his teammates defused the situation, but West did not forget the incident.

After graduating from South Side, West attended Bloomfield College and Cooper Union College in New York. He later served in the United States military before being honorably discharged. West was employed as a correspondent for the Newark Evening News and the New Jersey Afro-American newspapers. In 1966, at the age of 33, Calvin West became Newark’s first African American to be elected councilman-at-large. His sister, Larrie West Stalks, was the primary Black political operative for Mayor Hugh Addonizio, and managed all the support Calvin needed from the Mayor. Ironically, West won the election on the first ballot, and Addonizio sought support from West in his run-off election in 1966.

As a city councilman, West believed that working from “inside” the political system was the most effective way of uplifting Newark’s Black communities. “I decided, and my sister [Larrie West Stalks] decided,” West said, “that the only way to justify what tomorrow was going to bring for the youth, was through the ballot box.” Because of his emphasis on working from “within” the political system and his alliance with Mayor Addonizio, West often found himself at odds with the younger generation of Civil Rights and Black Power activists in the city. This younger generation thought that West and other Black political insiders with Addonizio were operatives in a politically corrupt and bankrupt system, though West argued, “I wanted to get on the inside so we could all be a part of it.”

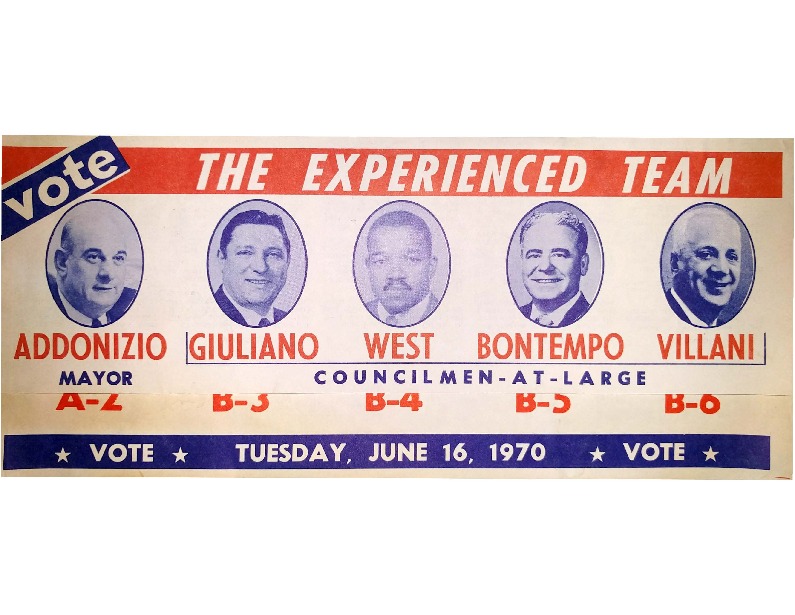

Calvin West was in opposition to most of the so-called “militants” and Black Power advocates in the 1960s, leading up to Ken Gibson’s election as mayor. He ran for a second term in 1970 on the ticket with Mayor Addonizio. He lost his seat on the City Council to Earl Harris, a nominee of the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention.

In 1986, Calvin West served as the personal aide and Chief Advisor to Newark’s second Black mayor, Sharpe James. Subsequently, West became the Executive Director of the North Jersey Office of the Governor, serving under the administrations of James McGreevy, Richard Cody, and Jon Corzine. He served the City of Orange Township as the personal aide and chief of staff to Mayor Joel Shain and also as Chief Advisor to Mayor Paul Monacelli as a member of the Orange Board of Education. Beginning in 1960, West participated in the highly-contested and successful presidential campaign efforts of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation.

Calvin West remarks at “The 1967 Newark Rebellion: Power and Politics, Before and After” Conference, October 1, 2016.

Junius Williams Interview with Calvin West, 2016.

Calvin West reflects upon his early experiences with racism and segregation growing up in Newark — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Calvin West describes his election as Newark’s first African American Councilman-at-Large in 1966. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Flyer from Calvin West’s 1970 campaign for re-election as Councilman-at-Large. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Portrait of Calvin West taken in 1966 by Newark photographer, Al Henderson. — Credit: Newark Public Library