Chapter Four Pages

Black Power and Cultural Nationalism

World War II kicked off the second Great Migration, as African Americans from the South sought better living conditions in Newark and other cities. Between 1940 and 1950, the African American population of Newark increased from 45,760 to 74,965—growing from 10.7% to 17.2% of the city’s total population. In many ways, this population influx marked a tipping point for recognition.

For most of Newark, the depression ended. “Help wanted “ signs went up. But African Americans could not always find a job. The New Jersey Afro-American wrote in 1941 that while contracts for nearly a billion and a half dollars in government defense orders have been placed with firms in New Jersey, the Urban League finds that these firms have steadfastly refused to hire colored workers.”

————

“Help wanted “ signs went up. But African Americans could not always find a job.

————

But some African Americans did find employment. Jobs for blacks in the Newark defense workforce improved from 4% in 1942, to 8.8% in 1943. With the overall economy booming, Newark’s downtown stores began hiring some African Americans as elevator operators and janitors. Large restaurants hired blacks as chefs, cooks and waiters—they could work, but not sit down to eat. The war years helped enhance the prospects of some, while still denying prosperity for the many.

Whites Begin to Leave

Around 1947, the white middle class started deserting Newark for the suburbs, along with the businesses that sustained them. The post World-War II boom was good for businesses for a while, but factories, schools, and streets had been neglected during the war. Overcrowding was a problem, especially in the ghettos. These conditions made the suburbs very attractive as alternatives to Newark.

The G.I. Bill of Rights and FHA loans made it easier for whites to buy a house, and brand new highways built by the federal government with taxpayers’ dollars made it easier to drive those new automobiles to the suburbs, in Essex County and further west. These same mortgages were unavailable to most African Americans; and most suburbs were off limits.

————

These same mortgages were unavailable to most African Americans; and most suburbs were off limits.

————

But Newark’s heterogeneous ethnic character remained intact in the early and mid-1950s. Newark was described as follows by writer Joseph Conforti:

The Germans had given way to the Irish who in 1950 shared political power with an Italian and a Jew. The ethnic division of the city could also be observed less directly. Many occupations were ethnically identifiable: the police and fire departments were overwhelmingly Irish; the construction trades were Italian; the merchants were largely Jewish, the small luncheonettes were Greek, the large businesses were owned and operated by WASPs, skilled craftsmen were likely to be German, and the factory operatives were Irish, Polish and Italian. Even the city’s taxicabs had ethnic identifications…yellow cabs were operated by the Irish, 20th Century cabs by Jews, Brown and White cabs by Italians, and Green cabs by blacks.

Newark’s Changing Demographics

Ghettoization continued in Newark. By 1940, the Third Ward (today’s Central Ward) alone contained more than 16,000 black residents. By 1944 nearly one third of the apartments and housing in the black areas were below the standards of minimum decency. Some houses still had outside bathrooms.

The slums were among the worst in the nation. The situation was particularly grim for African Americans, clustered on “the hill” just west of the Essex County Court House. Public Housing did not help a lot. There were 7 low-income projects finished before the war, but by 1946, there were 2,110 white families and only 623 black families in the buildings. Four of the projects housed no black people. The best low-rise public housing, such as Bradley Court, was reserved for whites; while the poorest units, such as F.D.R. Homes, were reserved for blacks. Ultimately, the majority of African Americans were steered into the growing number of high rise public housing which just happened to be built in the center city where black people had been confined beginning at the turn of the 20th century.

————

Four of the projects housed no black people.

————

The 1950 Census showed the trend in population increases for blacks, and decrease by whites. Newark’s total population rose only slightly from 429,760 in 1940 to 438,776 in 1950. Black residents had increased from 45,760 to 74,965—more than a 60% increase. When newspapers took a look at the faces of misery, increasingly they were black.

Even though the city began hemorrhaging jobs (250 manufacturers left between 1950-60; 1,300 manufactures left during the 1960s), the more dramatic change in the city’s socioeconomic structure was the rapidly changing composition of the city’s population.

African Americans were rapidly become politically and economically obsolete in a city where they would soon be in the majority. Segregation and discrimination by race and class defined Newark’s offering to the city’s newest immigrants.

Listen to the people speak about their experiences as newcomers to Newark below…

Amiri Baraka describes cultural nationalism in Newark, and the emergence of the Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN) and the Congress of Afrikan People (CAP). — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

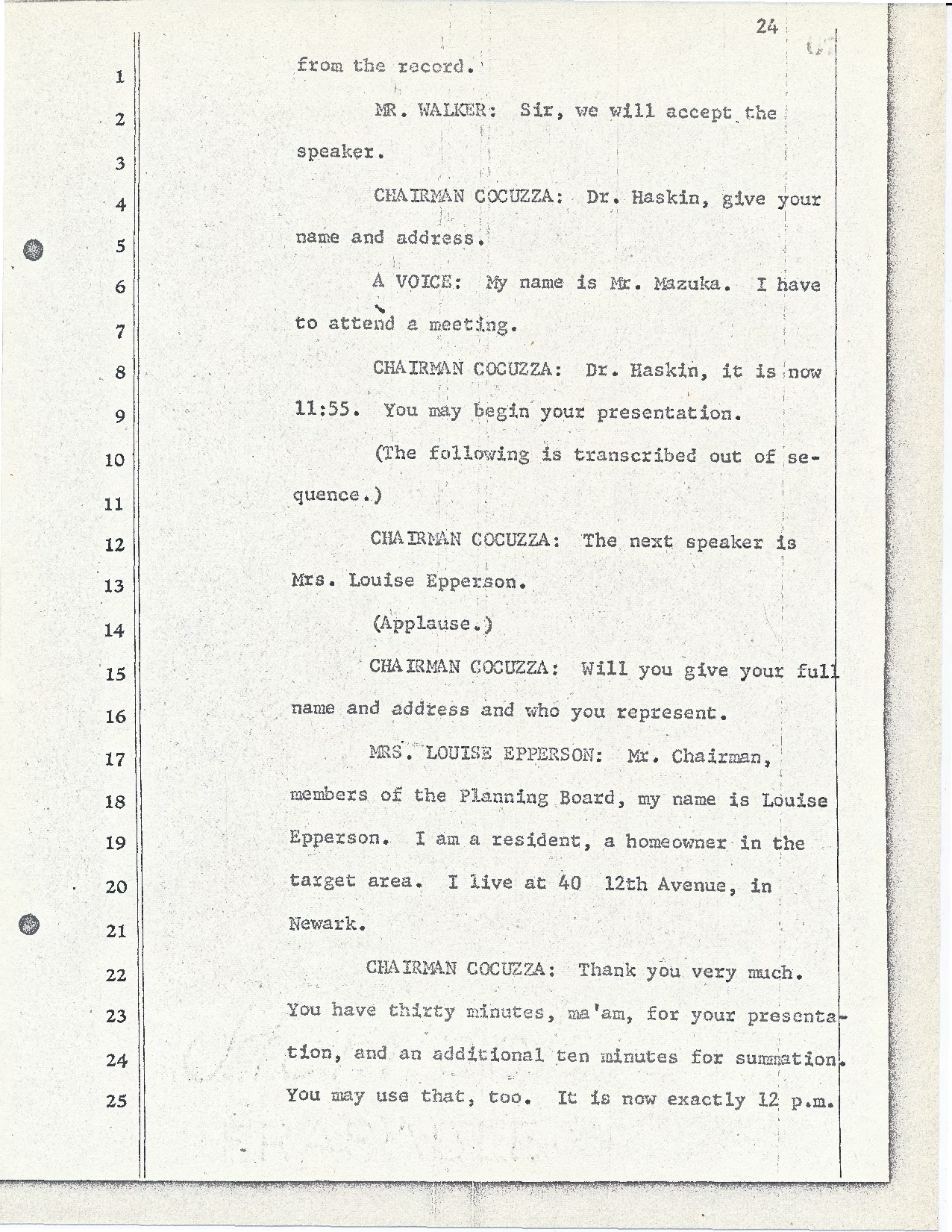

Transcript of Louise Epperson’s statement to the Central Planning Board on June 13, 1967 during the Medical School “blight hearings.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

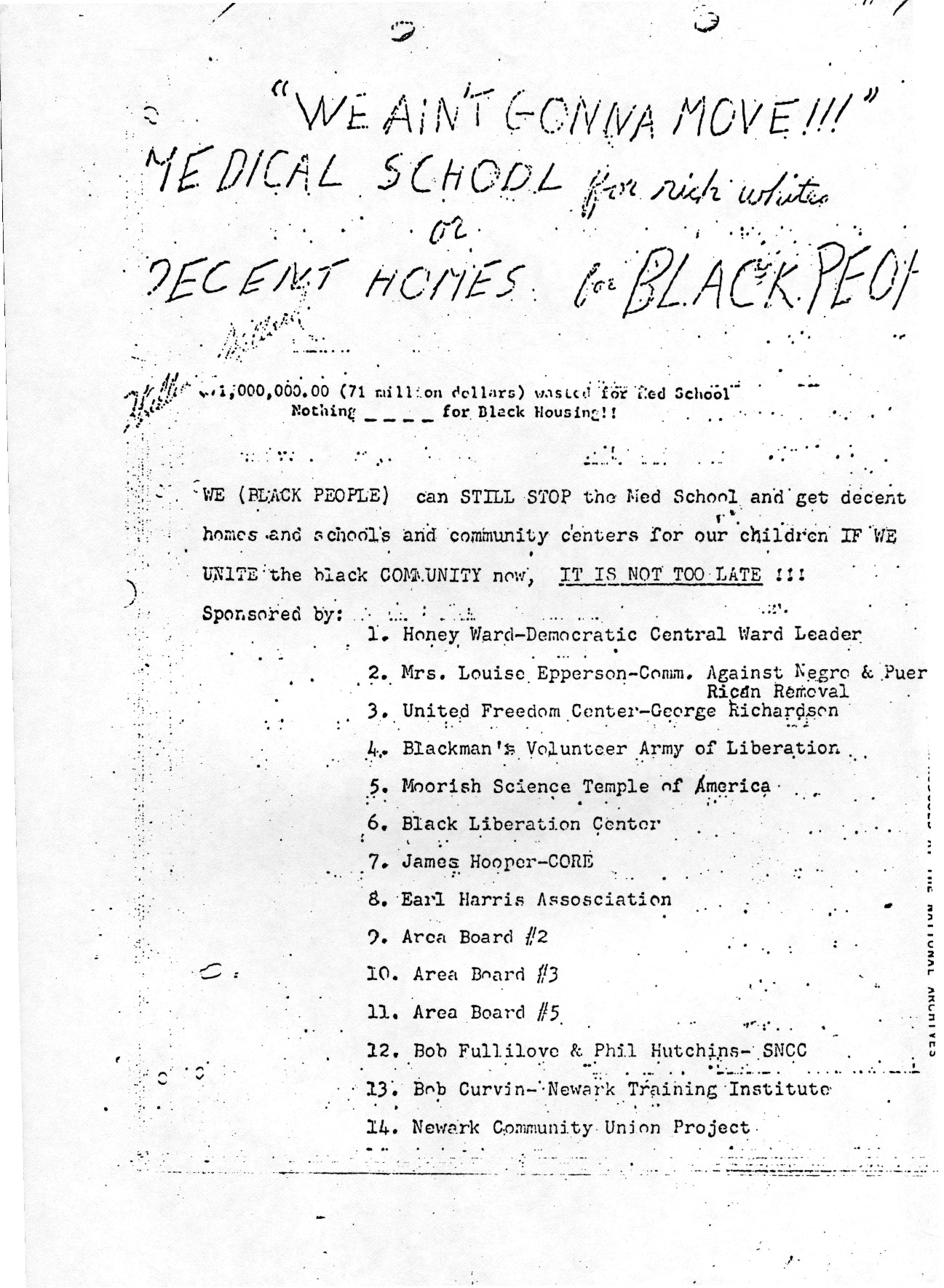

Flyer distributed to encourage community members to protest the seizure of land for the construction of a medical school in the Central Ward. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

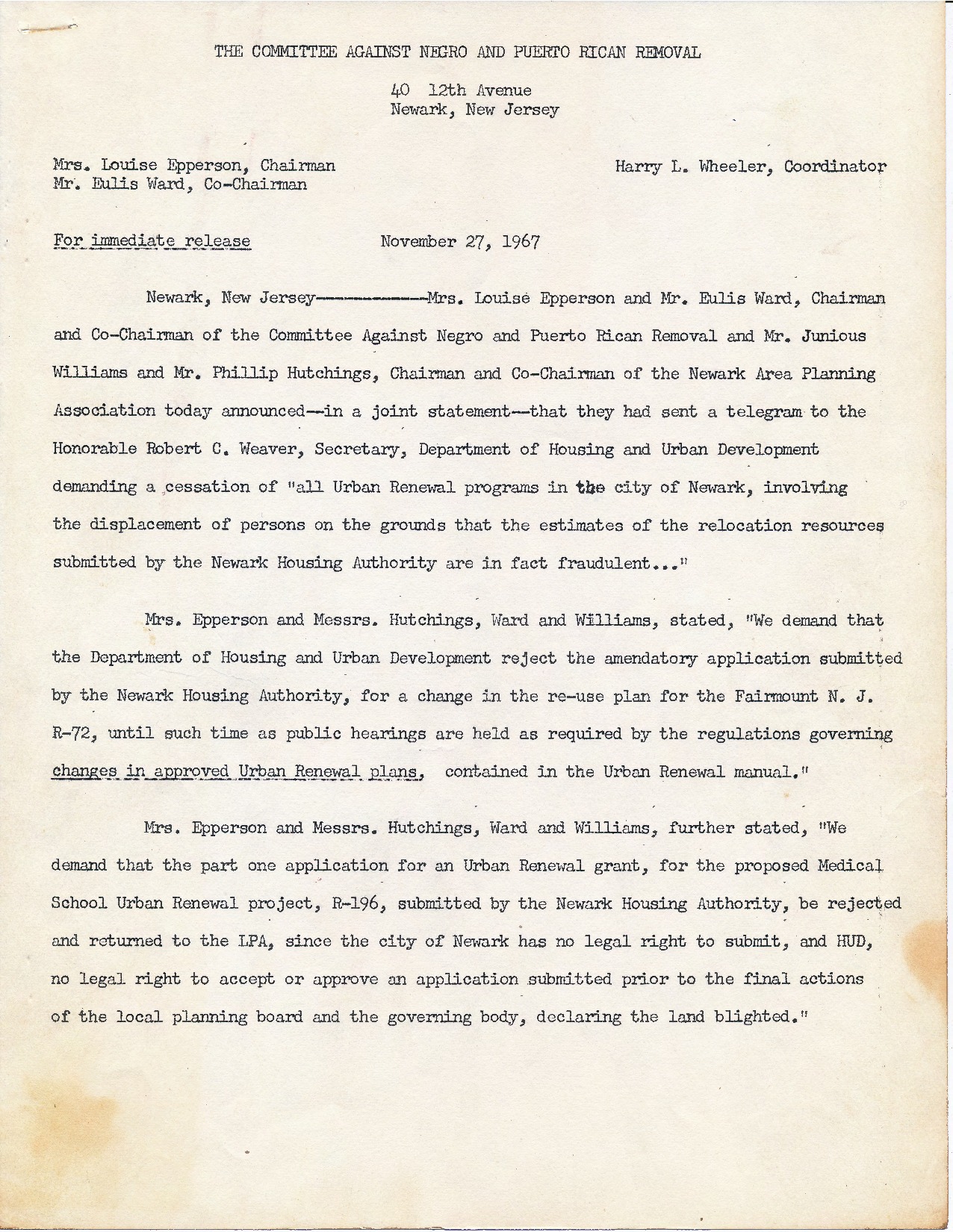

Letter from the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal to Robert C. Weaver demanding that all urban renewal projects in Newark be stopped. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives

Photograph from the PSEG archives of an African American repairman at work. — Credit: PSEG

A look inside the apartment of an African American family at 22 Clayton Street in Newark. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

A look inside the apartment of an African American family at 22 Clayton Street in Newark. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

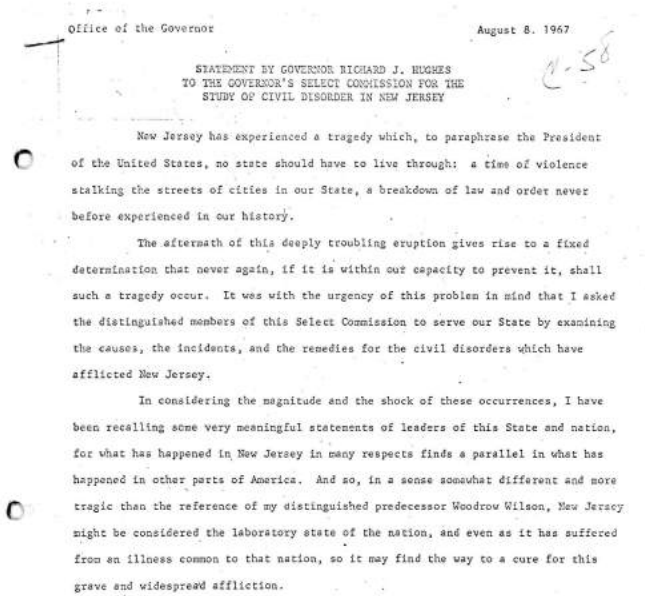

The Fight For Kawaida Towers

On August 8, 1967, New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes asked the members of the newly formed Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder to “examine the causes, the incidents, and the remedies for the civil disorders which have afflicted New Jersey.” Speaking to the ten-member Commission, Governor Hughes urged, “It is most important that the Commission…shall point the way to the remedies which must be adopted by New Jersey and by the nation to immunize our society from a repetition of these disasters.” With these instructions, the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder embarked on a five-month venture to study the deep-seated problems facing the City of Newark and issue a report on its findings to the city, state, and nation.

According to community activist Robert Curvin, who testified before the Commission, “The inquiry followed a model similar to that of a grand jury, where the building blocks of information based on facts, details, and credible stories from many different points of view and angles lead to a strong, powerful conclusion.” During its five-month operation, the Commission heard testimony from a cross-section of Newark residents, including civil rights activists, police officers, politicians, lawyers, clergy, community residents, and business owners.

After conducting 65 meetings and 106 interviews, the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder published its findings and recommendations in a two-hundred-page report titled Report for Action. In its report, the Commission concluded that the 1967 Newark rebellion resulted from the unwillingness of city and state governments to address longstanding issues of political, social, and economic inequality and oppression in the city.

The report consisted of three sections. The first, “Sources of Tension,” examined issues of discrimination and inequality in the areas such as politics, employment, housing, education, welfare, healthcare, and policing. The second, “The Disorders,” provided a chronological review of the 1967 Newark rebellion and critically analyzed the actions of law enforcement agencies during the rebellion. The third, “Recommendations,” presented the Commission’s suggestions on ways to address the critical issues of discrimination and inequality within the city, as well as policy recommendations for “the control of civil disorders.”

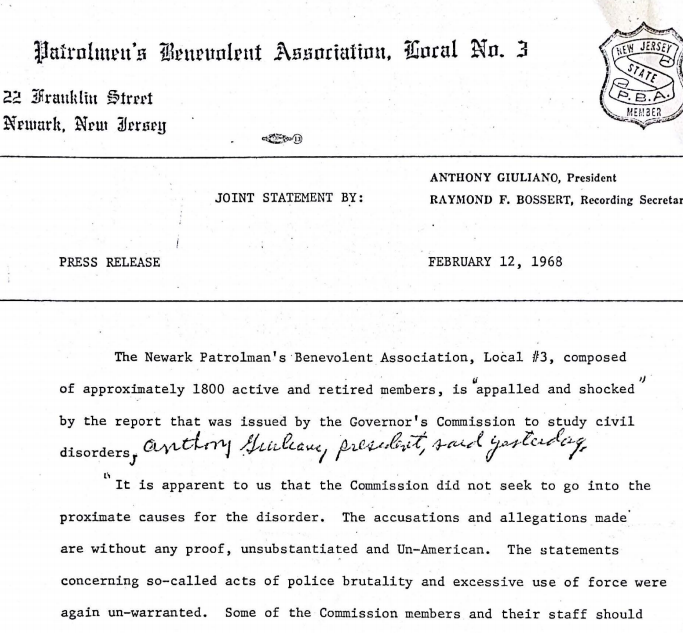

The Commission’s lengthy report was met by mixed responses in the city. To African-American community leaders, such as Reverend Kim Jefferson and future mayor Ken Gibson, the report was received positively. Jefferson called the report “a real and lasting contribution to the people of this state and indeed of our nation,” while Gibson endorsed the report and called for an additional commission to ensure implementation of the Commission’s recommendations. To members of law enforcement agencies, though, the report represented a direct attack on police. The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Associations of the city and state lashed out at the Commission’s “accusations and allegations” of police brutality, as well as its recommendation to create a civilian police review board.

Although the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder has been widely revered as “one of the most complete documents ever produced to investigate civil disorders at the state level,” most of its recommendations went unfulfilled. Of the ninety-nine recommendations made by the Commission, only twenty-six were actually implemented. Addressing the lack of action on the Commission’s recommendations a year after its publications, one of the members forewarned, “If we can accomplish a democratic redistribution of political power, the glory of that achievement will rest on us all. If we cannot or will not embark on such an undertaking, we may very well attend at the funeral of this city and the dreams of its desperate people.”

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation.

Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder, Report for Action.

Transcript of address given by Governor Richard J. Hughes to the Governor’s Select Commission for the Study of Civil Disorder in New Jersey on August 8, 1967. The Commission was convened by Governor Hughes to study “the causes, the incidents, and the remedies” for the 1967 Newark rebellion. The Governor’s Commission, also known as the Lilley Commission after its chair Robert Lilley, held months of hearings from Newark residents and later published its findings in Report for Action.

A February 12, 1968 press release from the Newark Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA) issued in response to the report of the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder. The Commission was convened by Governor Hughes to study “the causes, the incidents, and the remedies” for the 1967 Newark rebellion. The press release, prepared by Anthony Giuliano and Raymond Bossert, claimed “The accusations and allegations made [in the report] are without any proof, unsubstantiated and Un-American.”

Explore The Archives

Photograph from the PSEG archives of an African American repairman at work. — Credit: PSEG

A look inside the apartment of an African American family at 22 Clayton Street in Newark. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives

A look inside the apartment of an African American family at 22 Clayton Street in Newark. — Credit: WPA Photographs, NJ State Archives