Tom Hayden

In the fall of 1961, Tom Hayden sat in a jail cell in Albany, Georgia, writing what would later become the Port Huron Statement. Hayden, a recent graduate of the University of Michigan and field secretary for the student activist organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), had been arrested for his role in a nonviolent protest in Albany, just months after being beaten at a demonstration in McComb, MS. The Port Huron Statement, which Hayden began in that Albany jail cell, would become the manifesto for a new generation of student activists, inspired by “the Southern struggle against racial bigotry” and the Cold-War era threat of nuclear destruction.

As the southern Civil Rights Movement increased in size, pace, and militancy, SDS responded by establishing a new program called the Economic Research and Action Program (ERAP), which sought to create an “interracial movement of the poor” in impoverished northern urban communities.

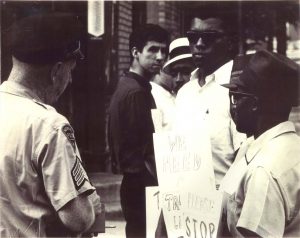

Once in Newark, Hayden and NCUP members sought to develop local leadership in struggles for civil rights and political empowerment in the city by organizing around landlord-tenant conflicts, police brutality, unscrupulous retail storeowners, and urban renewal. Hayden was involved in a variety of civil rights activities, such as: the struggle for a traffic light at a busy intersection, rent strike demonstrations, insurgent political campaigns, struggles for community control of anti-poverty agencies, and negotiations with government officials to remove the State Police and National Guard during the 1967 Newark rebellion.

Tom Hayden was a polarizing figure in Newark during his time there from 1964-1967. Under surveillance by local police and FBI agencies, city officials saw Hayden as an “outside agitator” and a “troublemaker.” Many in Newark’s Black communities also had mixed feelings about Hayden, who, as a white outsider, some saw as being for the people, but not of the people. However, Hayden’s contributions to the city can be seen through the development and legacies of “indigenous leaders” that NCUP helped to mobilize and empower, like Bessie Smith, Jesse Allen, and George Fontaine.

NCUP was not the first community group to challenge the power structure in Newark, but the first in the 1960s to organize poor and working class people on a consistent basis and develop local leadership whose work lasted well into the 1970s.

Tom Hayden left Newark shortly after the 1967 rebellion. He wrote the then definitive work on the rebellion entitled Rebellion in Newark: Official Violence and Ghetto Response. After leaving Newark, Hayden became an icon in the anti-Vietnam War movement. He was later elected as an Assemblyman and State Senator in California.

References:

Mark Hamilton Lytle, America’s Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era From Elvis to the Fall of Richard Nixon

Students for a Democratic Society, The Port Huron Statement

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Newark residents, politicians, journalists, and civil rights activists reflect upon their experiences with Tom Hayden. (See Vimeo link for credits)

Pamphlet distributed by the SDS Economic Research Action Project (ERAP), providing an introduction and overview of the project. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

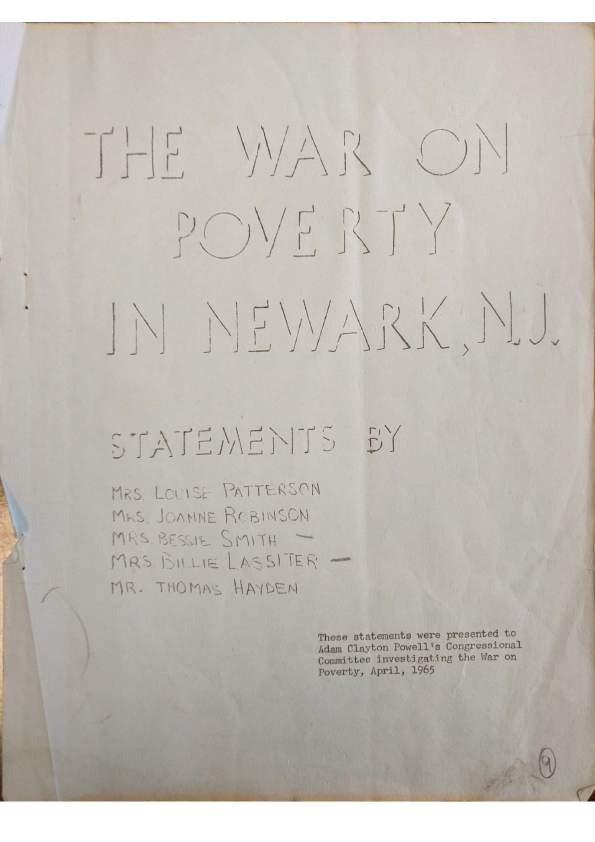

Collection of statements by NCUP members presented in April, 1965 to Adam Clayton Powell’s Congressional Committee investigating the War on Poverty. — Credit: Newark Public Library