Police and the Black Community

One of the most pervasive and contentious aspects of northern-style Jim Crow society was the widespread presence of discriminatory police practices. Though Newark’s African American and Puerto Rican populations had protested mistreatment from the city’s predominantly white police department for years, the 1960s represented a new chapter in the struggle for a fair and just criminal justice system.

In 1959, the Mayor’s Commission on Group Relations published Newark: A City in Transition, a report that presented the results of a broad survey of the city’s residents on “group relations” in Newark. The survey asked residents about group relations in various sectors of city life, including housing, education, employment, social life, and politics. One of the most significant findings of the survey, however, was in regards to the relationships that existed between the mostly-white police force and the city’s Black and Puerto Rican populations.

Until the eruption of the Newark rebellion in 1967, there were only 145 African American police officers among a department of 1,512, with most of the force being of Irish and Italian descent. The consequences of this racial gap was clear in the Mayor’s Commission Report, which stated, “stories about police discrimination—physical abuse, unfair arrests, and, to a lesser extent, laxness in the protection of Negroes—are widespread, and have been heard by almost half the Negro community.” Furthermore, the report continued, “Belief in stories about mistreatment of Negroes at the hands of the agency whose primary function is to protect citizens, the police, is so widespread among Negroes as to present a very real problem for the City of Newark.”

As the Commission’s report concluded, the mistreatment that Newark’s Black and Puerto Rican communities experienced at the hands of the Newark Police Department ranged from a neglectful lack of police protection to outright police brutality. Complaints of verbal and physical abuse from police officers were widespread in Newark’s Black and Latino communities. Incidents of excessive use of police violence were constantly in the public eye, as well as unnecessary stops, humiliating searches, and other racist misuse of power.

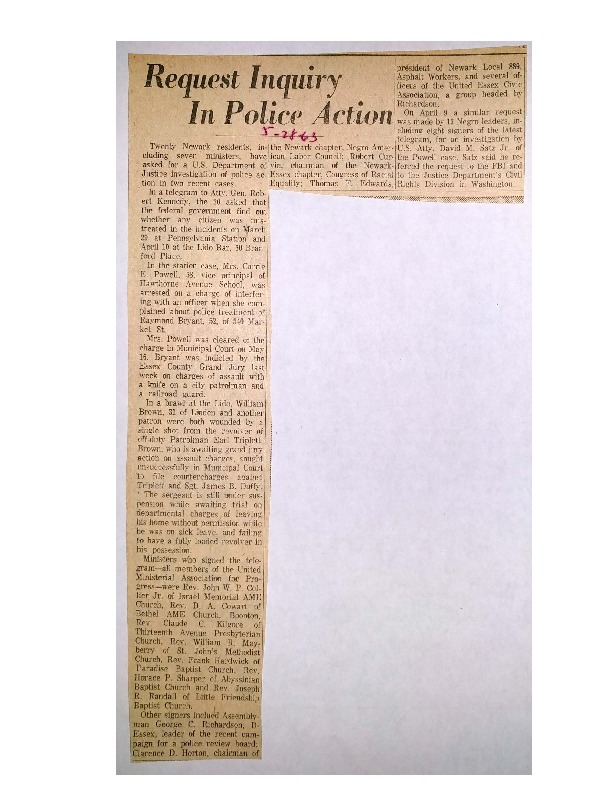

In the early 1960s, four particular cases of police brutality garnered extensive media coverage. In March of 1963, Mrs. Carrie Powell, 58-year-old vice-principal of Hawthorne Avenue School, was verbally abused and arrested in Penn Station after she protested a police officer beating a man who was being detained there. A few weeks later, an off-duty patrolman shot William Brown and another man outside of the Lido Bar, where a scuffle had broken out. Shortly thereafter, a pregnant Black woman was alleged to have beaten by a Newark patrolman, sparking demonstrations outside of City Hall by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The highest profile case of brutality that year, though, came when police and construction workers attacked peaceful protestors who were demanding access to jobs for Black workers at the Barringer High School construction site.

These high-profile brutality cases led to demands for a police review board, to hold police officers accountable for misconduct. George Richardson, who had delivered a petition with 18,000 signatures to Mayor Addonizio demanding a police review board a year earlier, formed a Citizens Watchdog Committee to combat police brutality. Under the leadership of Bob Curvin and Fred Means, CORE took a leading role in organizing the community against police brutality, leading marches, pickets, and mass rallies in the city to demand accountability and oversight.

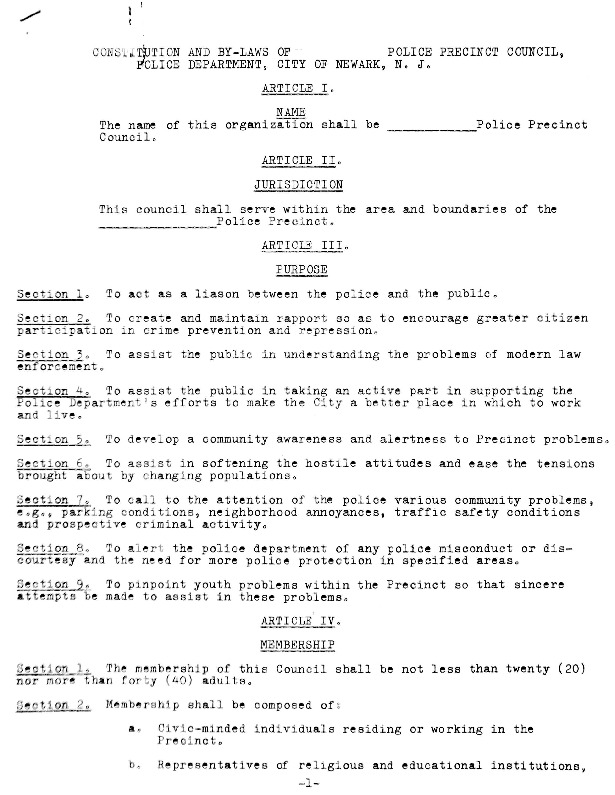

Despite calls from Richardson, CORE, the ACLU, and the Newark Human Rights Commission, Mayor Addonizio refused to create the review board. Instead, he announced that “precinct councils” would be formed to promote understanding between the police department and residents of the city. While weakly promoting police-community relations, the Addonizio administration relied upon the police force to put down demonstrations aimed at City Hall, turning a blind eye to their heavy-handed use of authority. Civil rights activists and organizations became targets for police surveillance and violence, and suffered from political retribution for challenging the enforcement arm of white supremacy in the city. Addonizio fired George Richardson from his city job in 1963 for participating in a CORE picket line at City Hall to demand a civilian review board.

Struggles for police reform continued in 1964 following the deaths of Bernard Rich and Benjamin Bryant, two Black men who were beaten while in police custody. Although a grand jury and the Newark NAACP launched investigations into Bryant’s death and the non-fatal shooting of another Black man, Leroy King, Newark’s Black community found no justice from City Hall. These continued acts of unchecked brutality left a perpetual mark of distrust and anger in the psyche of the people, and tensions came to a head in 1965 with the fatal shooting of Lester Long, Jr.

Scroll down to find out more…

References:

Kevin Mumford, Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America

United Community Corporation (UCC) member Edna Thomas describes police abuse of Black women and the roles of Black police officers in supporting struggles to reform police practices. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A 1959 report from the Mayor’s Commission on Group Relations on “group relations” in Newark. Policing was a commonly discussed issue among the city’s Black residents. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Newark organizer and politician George Richardson describes incidents of police brutality in 1963 and the series of demonstrations that followed at City Hall. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Constitution and By-Laws for Newark Police Precinct Councils. The precinct councils were established as an alternative to a “police advisory board,” which Mayor Addonizio rejected in April 1963. –Credit: Newark Public Library

Explore The Archives

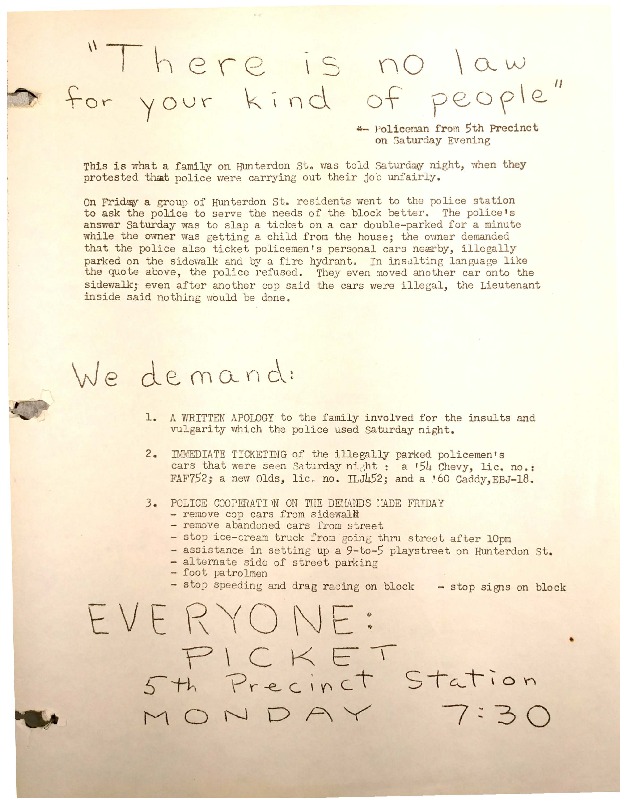

Flyer distributed by the Clinton Hill Neighborhood Council announcing a picket at the Fifth Precinct on June 29, 1964. The protest was planned in response to insulting remarks made by police to residents of Hunterdon Street after they requested fair treatment and better service by police in their neighborhood. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Clip from an interview with community leader Hilda Hidalgo, in which she describes the state of relations between police and Black and Puerto Rican communities in Newark during the 1960s. Discriminatory policing was one of the most contentious issues in Newark, as in many northern cities, during the 1960s. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member Mary Smith, in which she describes a particular case of police brutality. Smith remembers receiving a call from a parent about their son being arrested and later seeing the young man in jail “very badly beaten.” — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member Edna Thomas, in which she describes the particular abuses that Black women suffered from Newark policemen. Thomas also discusses the roles of Black police officers in supporting and protecting Black citizens in their struggles to reform police practices. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from the film “We Got to Live Here,” in which an anonymous person describes being picked up by Newark police and beaten within the police station. There are numerous reports of Newark police beating suspects while in custody during the 1960s, most notably when Benjamin Bryant and Bernard Rich were killed while in custody in 1964 and 1965, respectively. — Credit: Robert Machover

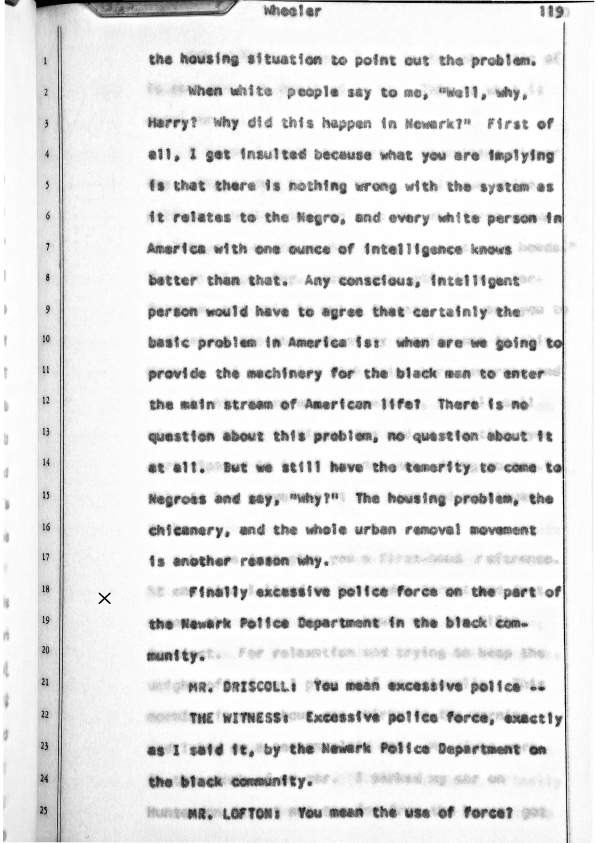

Excerpt from the testimony of community leader Harry Wheeler before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder on December 8, 1967. In this excerpt, Mr. Wheeler discusses the abusive practices of the Newark Police Department and describes a particular instance when he was accosted by Newark police officers. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

Unmarked newspaper article from May 28, 1963 covering two recent cases of alleged police misconduct. The first resulted from the arrest and mistreatment of Mrs. Carrie Powell, vice principal of Hawthorne Avenue School, as she objected to the beating of a suspect by Newark police in Penn Station. The second resulted from a police shooting at the Lido Bar after an off-duty patrolman responded to a “brawl” there. These two instances are credited as propelling the continued struggle for a police review board in Newark. — Credit: Newark Public Library

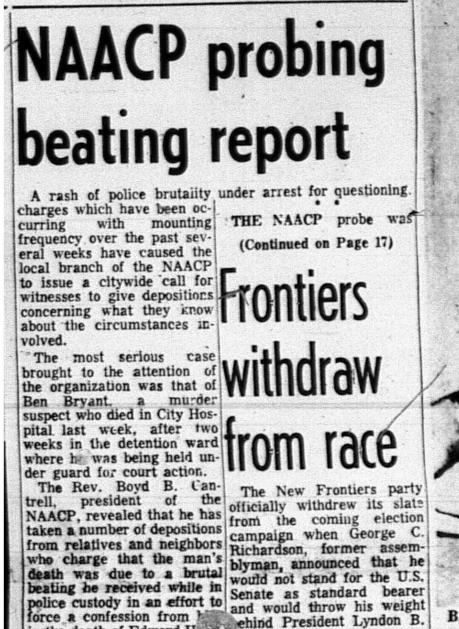

Article from the New Jersey Afro-American on July 18, 1964 covering an NAACP probe of recent allegations of police brutality, specifically the death of Benjamin Bryant while in police custody. Other cases of recent police misconduct directed at Black residents of Newark are also decribed in brief. In response to these allegations of brutality, the reporter claims that “unless some immediate steps are taken to bring Newark’s ‘trigger and club happy’ police under control it is feared that the colored community will be the scene of uncontrolled violence as colored citizens will seek some means of protecting themselves from abuse.” — Credit: New Jersey Afro-American

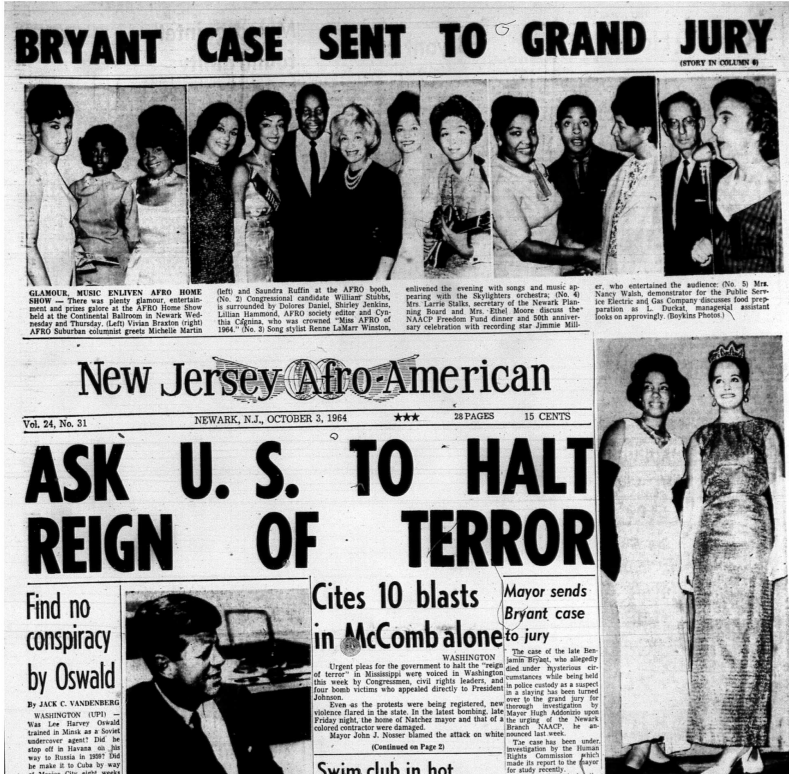

Article from the New Jersey Afro-American on October 3, 1964 covering the case of Benjamin Bryant, who “died under mysterious circumstances while being held in police custody.” The article contains an excerpt from Mayor Addonizio’s statement to the press regarding the case and describes the actions taken by city officials to investigate Bryant’s death. After city officials side-stepped community efforts for a police review board in 1963, Bryant’s death and later instances of police abuses renewed demands for the establishment of a review board. — Credit: New Jersey Afro-American

The Shooting of Lester Long

The fatal shooting of Lester Long, Jr. in 1965 by Newark Patrolman Henry Martinez was one of the most explosive cases of alleged police brutality in the city’s history. The night of June 11th, 22-year-old Lester Long was driving down Broadway with a friend when they passed by an unmarked police car traveling in the opposite direction. After crossing paths with Long’s black 1955 Chevrolet, the two officers, William Provost and Henry Martinez, made a U-turn when they noticed the car’s loud muffler. The officers followed Long’s car down Broadway for a short distance until he pulled over at the corner of Oriental Place. According to police reports, Long gave the officers a suspicious driver’s license, so Martinez placed him in the back of the police car while they called in a record check on him. After finding that Long was wanted on contempt of court charges for unanswered traffic violations, the officers decided to take him to the precinct and called for a tow truck to come get Long’s car.

Around 2:00 AM, while the officers waited for the tow truck to arrive with Long in the back seat, the Happy Inn Tavern up the block closed for the night and patrons spilled onto the sidewalk near the corner of Broadway and Oriental. At this point, according to the officers, Long became combative when Martinez informed him that he was under arrest and would need to be searched. Martinez said that when he reached back from the driver seat to pat down Long’s pants, the man pulled out a knife and attempted to slash at him, cutting Provost in the process. Long then bolted from the car, running across Broadway toward the crowd that had gathered about 10 yards away. As Long ran, Martinez jumped out of the car, took two steps, raised his revolver, and fired. The bullet struck Long in the back of his head and the 22-year-old collapsed on the sidewalk in full view of the crowd.

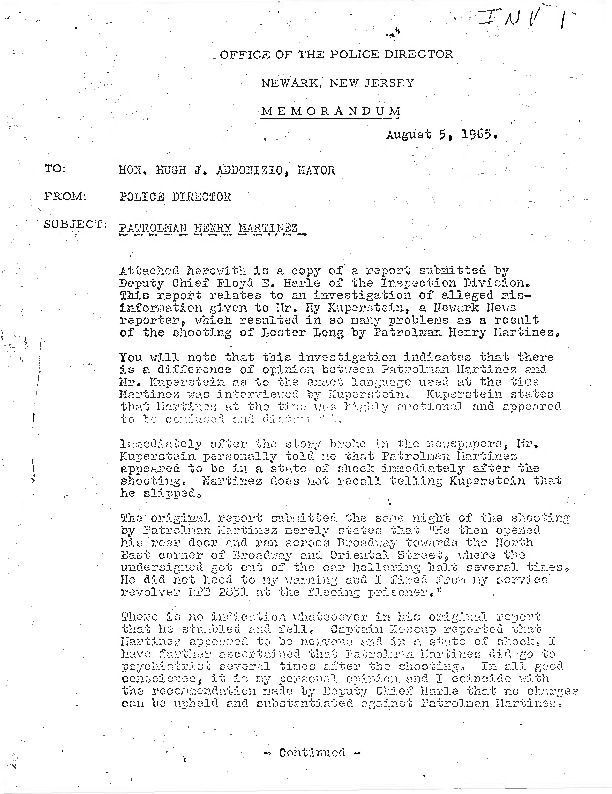

In the aftermath of the killing of Lester Long, Martinez gave conflicting statements about the shooting. In a statement given to Newark Evening News reporter Hy Kuperstein later that day, Martinez said that he had lost his balance when he got out of the car and didn’t mean to shoot Long. “The gun suddenly went off,” Martinez was quoted as saying, “I wasn’t trying to shoot him but he was hit.” However, in the police report, Martinez wrote that he “got out of the car hollering halt several times. He did not heed to my warning and I fired one shot from my service revolver.”

Immediately after the shooting, the Newark-Essex Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) found five witnesses to the killing and took sworn depositions with the help of a local attorney. This testimony contradicted several key aspects of the statements given by Martinez. First, the witnesses testified that Long did not have a knife, as the police report stated, when he ran from the patrol car. Second, the witnesses observed that the officers were wearing short-sleeve shirts, and neither appeared to have been cut by the alleged knife attack in the car. Third, the witnesses said that Martinez had never ordered Long to halt. The Grand Jury that heard the case, however, found no cause for indictment and Martinez returned to the force after a very brief suspension.

The brutal shooting of Lester Long sparked massive protests in the city that gained national attention. Martinez was never suspended and Newark’s Black community was furious. “I spent countless hours out there trying to prevent a riot,” CORE leader Bob Curvin said, “These people had all that kind of nonsense they could stand.” Civil rights groups like CORE and the Newark Community Union Project launched a series of demonstrations throughout the summer, including mass marches and sit-ins, to protest police brutality and demand a police review board. The protests brought CORE national director, James Farmer, into the city for a mass march, rally, and sit-in at City Hall, where 10 were arrested.

Rather than accepting community demands for a review board after the brutal shooting, city officials, police officers, and white citizens in Newark dug-in their heels and fought adamantly against police reform. After the CORE mass march, Farmer was one of ten leaders sued for libel by Henry Martinez because of flyers that were distributed calling the officer a “murderer.” Additionally, a group of angry white citizens, including police officers and the police union formed a group called United Citizens Against a Police Review Board, which held a 5,000-person march as a counter-protest to Farmer’s march and picketed at City Hall for five days. These protests demanding “law and order” showed the depths of white resistance to Black equality in Newark, and gave rise to a militant white backlash that grew more intense as the decade went on.

At the end of July, the Newark Human Rights Commission, which had already declared no wrongdoing on the part of Martinez, held a series of public hearings about a potential review board. After hearing 44 speakers and gathering 600 pages of testimony, the majority-white Commission was split 6-6 on the creation of a review board, and Mayor Addonizio subsequently rejected the board. Addonizio, who claimed that a review board would not improve relations between the police and Black community, announced that all future allegations of police abuse would be forwarded to the FBI—a move seen as toothless by most civil rights leaders in the city, since the FBI had no authority to bring any charges against police. The Mayor also ordered the establishment of Precinct Councils, a citizen observer program, and a Human Relations Institute to improve police-community relations. All of these measures were ineffective in curbing police abuse of Black and Latino communities in Newark, and were seen by most as siding with police over citizens.

Despite major protest activities by civil rights organizations to end police brutality in Newark, meaningful police reform was never achieved in the 1960s. Lester Long, Jr. was the first of four Black men to be killed by Newark Police from June through December 1965, and other high-profile assaults continued in the following years. As demands for police accountability and reform continued to build, city officials, the Newark Police Department, and white citizens continued to resist the efforts of civil rights organizations to end racist policing in Newark. These struggles came to a head on July 12, 1967, when the beating and arrest of Black taxi driver John Smith sparked the 1967 Newark Rebellion.

Henry Martinez was later elected to the City Council, and it would be over 50 years until the city finally created a Civilian Complaint Review Board in 2016.

References:

Ronald Porambo, No Cause For Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark

Troy M. Pearsall, “Police Relations with the African-American Community in Newark, 1957-1967,” in Newark: The Durable City, ed. Stanley Winters

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation member James Walker, in which he describes witnessing the police shooting of Lester Long on June 12, 1965. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

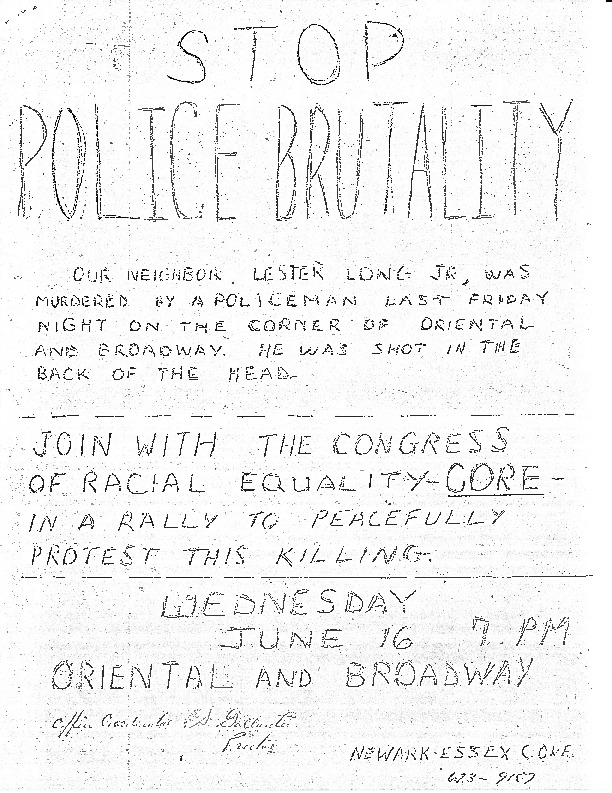

Flyer distributed by the Newark branch of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) announcing a rally to protest the killing of Lester Long by Newark policeman Henry Martinez. — Credit: Junius Williams Papers

Clip from an interview with Donald Malafronte, an aide to Mayor Addonizio, in which he discusses the fallout from the shooting of Lester Long in the summer of 1965. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Reports from the Newark Police Department detailing their investigation into the fatal shooting of Lester Long. Inconsistencies in the different accounts of the shooting given by patrolman Henry Martinez caused an uproar in the city. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Newark-Essex CORE chairman Fred Means speaks at a press conference about the fatal shooting of Lester Long in 1965. At his left, is James Farmer, executive director of the national office of CORE. — Credit: Fred Means Collection

Explore The Archives

Clip from an interview with Newark Evening News reporter Doug Eldridge, in which he discusses cases of alleged police brutality and the struggle for a police review board in the mid-1960s. The fatal shooting of Lester Long by Newark Patrolman Henry Martinez in June 1965 reinvigorated demands for a police review board from the city’s Black and Puerto Rican communities. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from a panel discussion during “The 1967 Newark Rebellion: Power and Politics, Before and After,” a two-day conference held in the Paul Robeson Campus Center at Rutgers University-Newark on October 1, 2016. In this clip, Fred Means, former chair of the Newark Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), discusses police brutality in Newark and CORE’s struggles for a police review board in 1965. — Videography: DreamPlay Media

Clip from an interview with Donald Malafronte, an aide to Mayor Addonizio, in which he discusses Mayor Addonizio’s responses to police-community relations after rejecting a proposed police review board in 1965. These responses included the establishment of a human relations training institute for police officers, as well as a citizen-observer program. The programs were largely ineffective and community demands for police accountability continued throughout the 1960s and beyond in the face of continuous allegations of police brutality. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from an interview with United Community Corporation (UCC) member Mary Smith, in which she discusses the struggles to establish a police review board in response to cases of police brutality. After Mayor Addonizio rejected a proposed review board for the second time in as many years in 1965, he instituted alternative programs to improve police-community relations, such as a citizen-observer program. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Excerpt from the testimony of community leader Harry Wheeler before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder on December 8, 1967. In this excerpt, Mr. Wheeler discusses the abusive practices of the Newark Police Department and describes a particular instance when he was accosted by Newark police officers. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository