Earl Harris

Earl Harris was one of the first Black men elected to county office as a Republican Freeholder for Essex County. He became a Democrat, supported Hugh Addonizio in his 1962 mayoral campaign, and served as an aide during Addonizio’s first administration. In return for his support, Harris later said, “Hughie told me that I could have the South Ward.” When Harris ran in 1966 against Lee Bernstein for City Councilman of the South Ward, however, his campaign cars were routinely ticketed and his staff members were threatened and intimidated by police. Harris went on to lose the race in the run-off election.

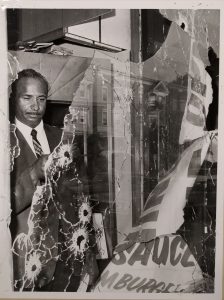

Subsequently, Harris abandoned his support for Addonizio and was an active voice in Newark’s struggles for civil and human rights. He routinely spoke out about police abuse, as well as urban renewal during the Medical School Fight. During the 1967 rebellion, Harris and other leaders acted as intermediaries between Newark’s Black communities and city officials in attempts to quell the disturbances. Their efforts had little impact on city officials, however, and Harris’s restaurant on Elizabeth Avenue was shot up by State Police and Newark Police days later. The restaurant was not yet open for business, but the windows were shot out and the equipment shot and destroyed, causing Harris to lose his investments in the store, for which he was never reimbursed by the state.

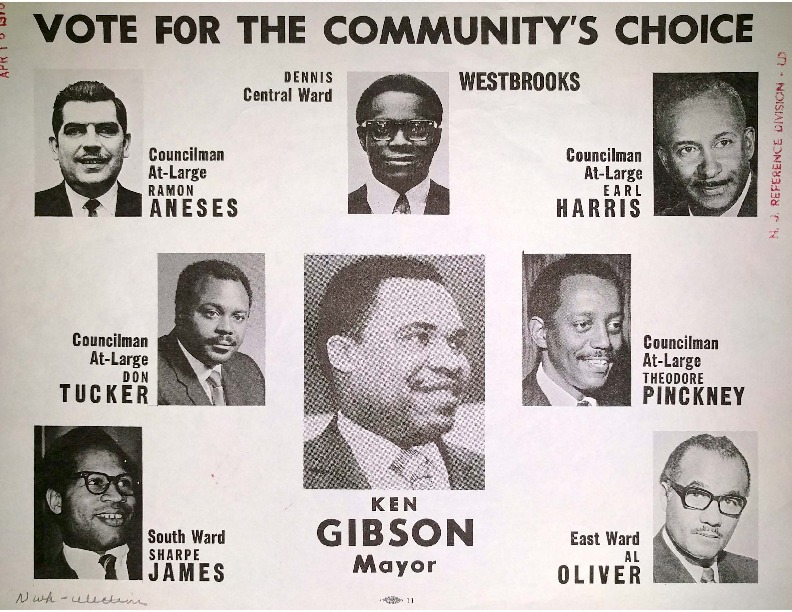

In the wake of the rebellion, Harris joined the United Brothers, a newly formed political organization aimed at creating a Black united front to win the 1970 mayoral and city council elections. At the Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention in 1969, Harris was nominated to run on the “Community Choice” ticket for the councilman-at-large contest. When rumors abounded that Mayor Addonizio’s people were paying off individuals to cast doubt on a Black victory on election day, Harris came up with a slogan that resonated from sound cars: “You can take the man’s money, but vote for the brothers.” Mayor Addonizio retaliated by having Harris arrested mid-day during the 1970 campaign on High Street for unpaid parking tickets.

Harris won a seat on the City Council in that 1970 election, finishing fourth among the at-large candidates, and was the only Black at-large candidate to be elected. Harris later went on to become the first Black President of the Newark City Council in 1974.

As president of the City Council, Harris clashed often with Mayor Ken Gibson; and with Amiri Baraka, his former supporter in the 1970 election, over the proposed Kawaida Towers construction in the North Ward. Harris led the charge to deny a tax abatement for the housing project, even going as far as ordering the arrest of Baraka, his wife Amina, and five others during a City Council meeting.

Harris went on to serve on the city council until 1982, when he ran unsuccessfully for Mayor against Ken Gibson, Joe Frisina, and Junius Williams. Gibson defeated Harris in a run-off campaign. Harris died in 2007, never having achieved his ultimate quest for the position of Mayor of Newark.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Komozi Woodard, A Nation Within a Nation

Campaign flyer for the 1970 Mayoral and City Council elections in Newark. “The Community’s Choice” was nominated during the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Convention. –Credit: Newark Public Library

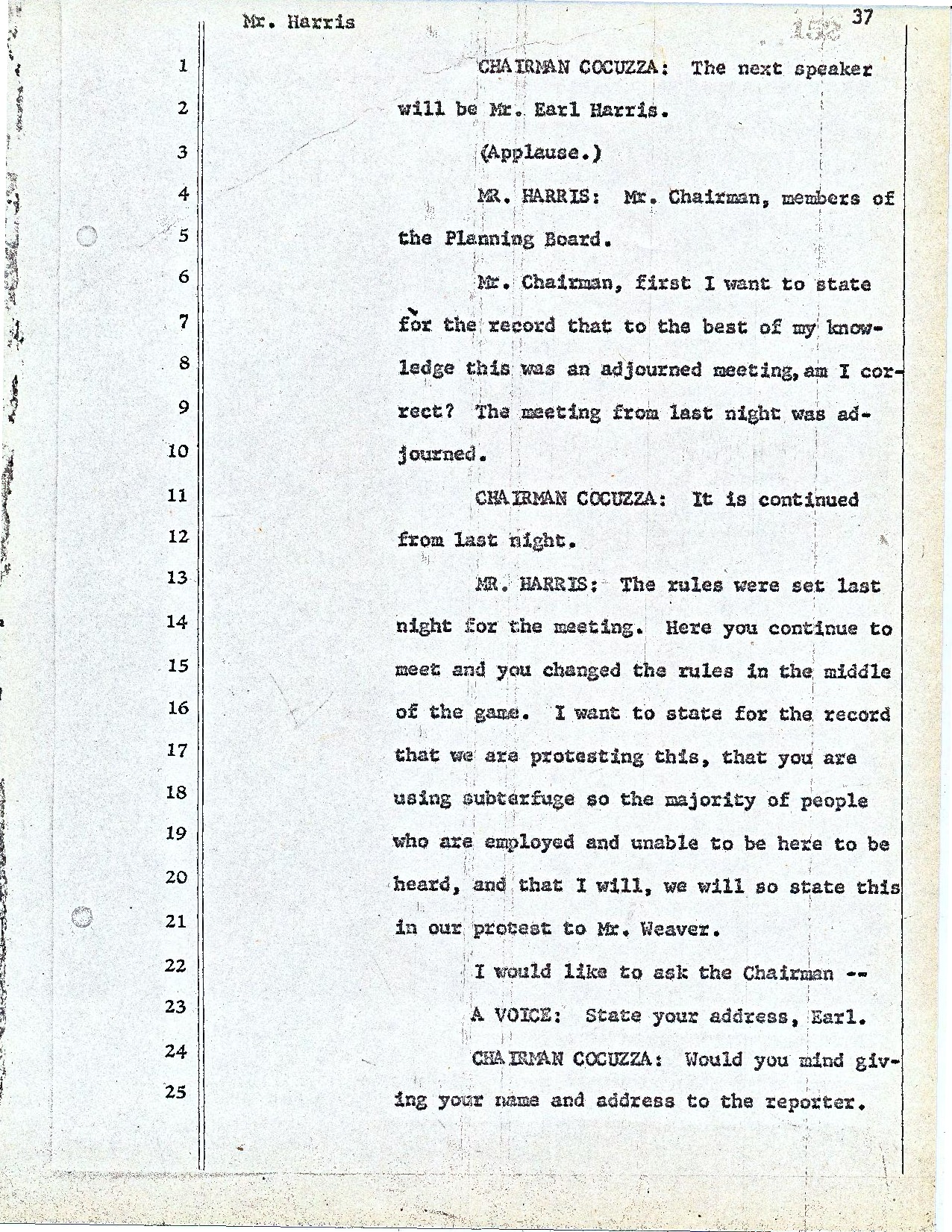

Transcript of Earl Harris’s statement to the Central Planning Board on June 13, 1967 during the Medical School “blight hearings.” — Credit: Newark Public Library

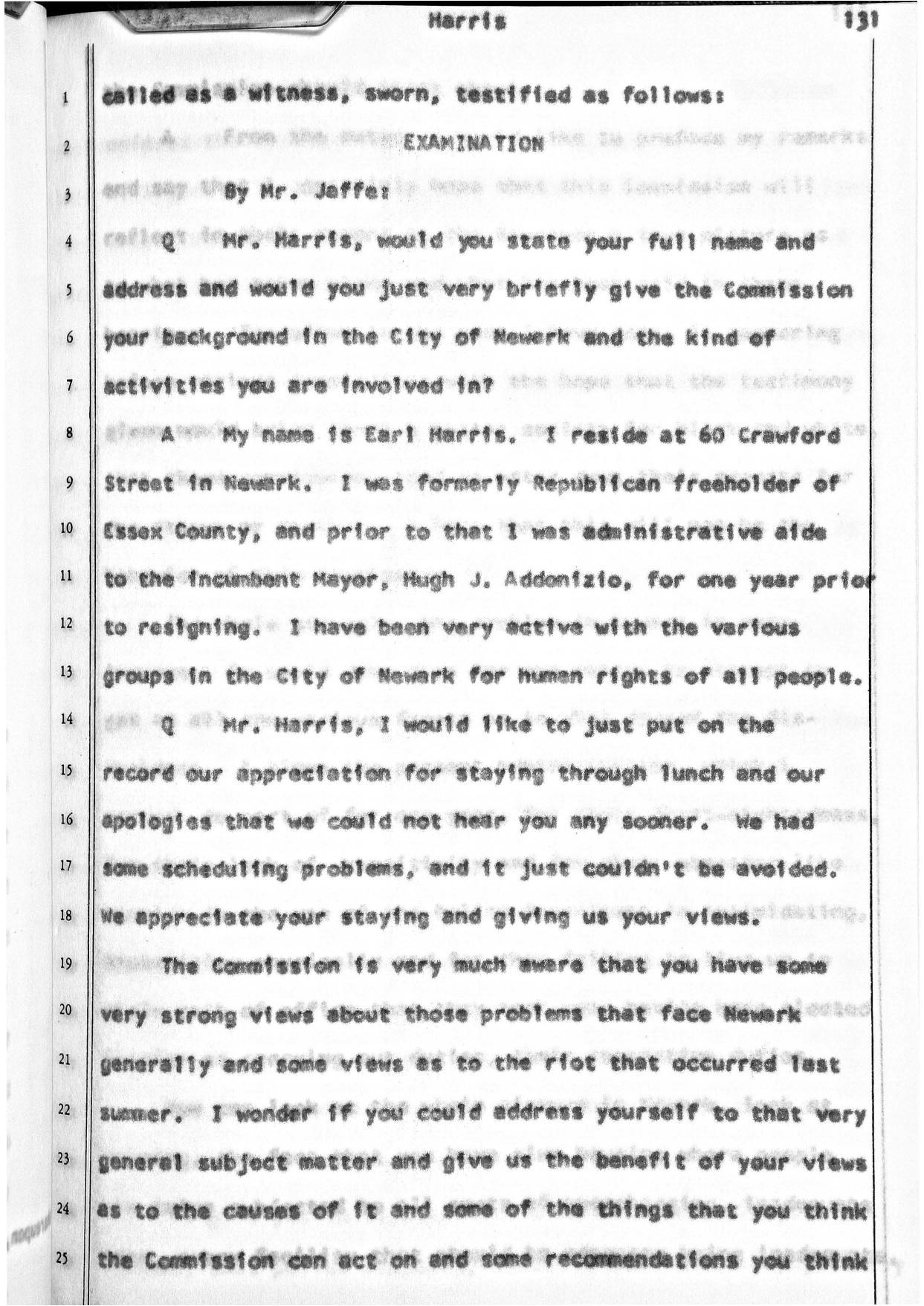

Testimony given by Earl Harris to the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders on Dec. 8, 1967. The Commission was formed to investigate causes of the 1967 Newark rebellion. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository