Willie Wright

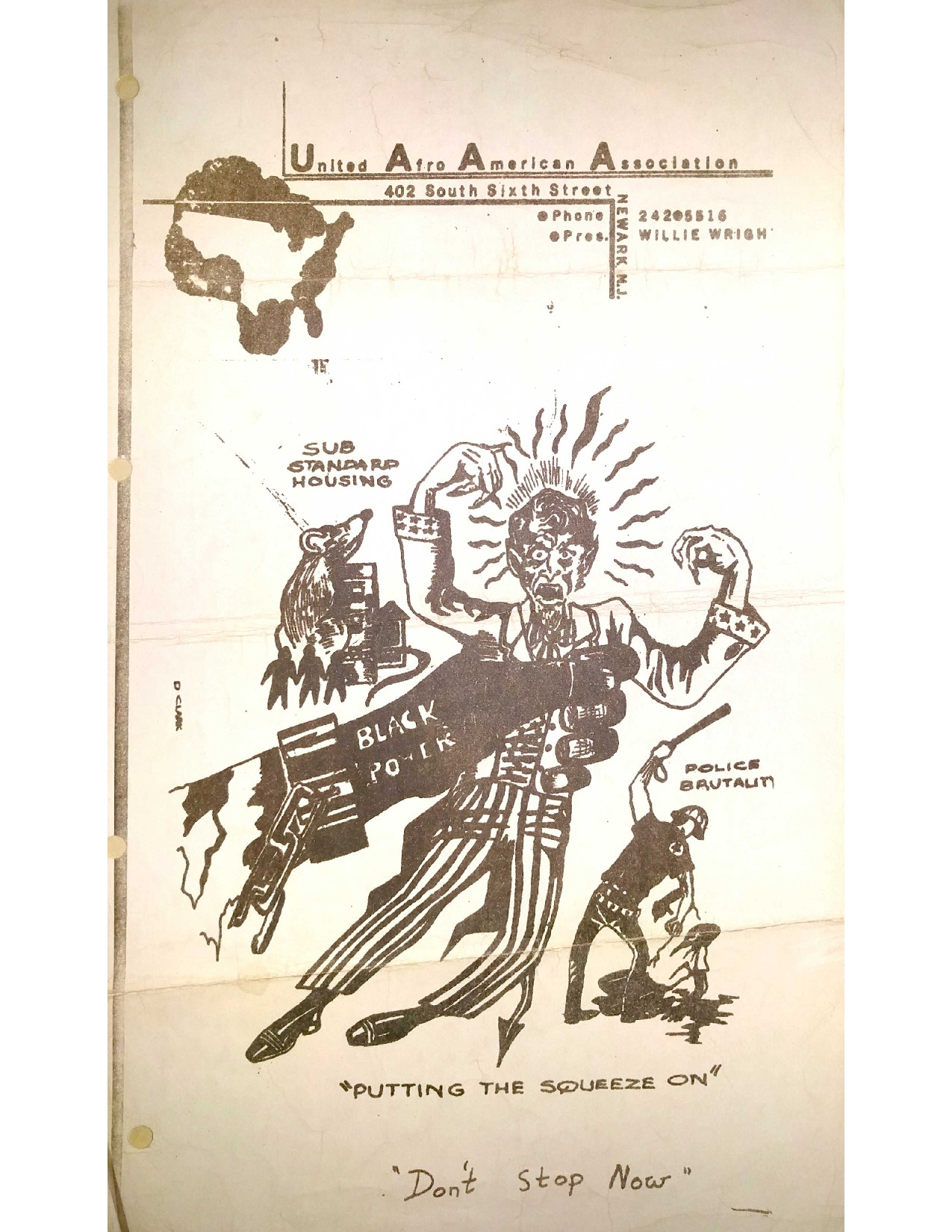

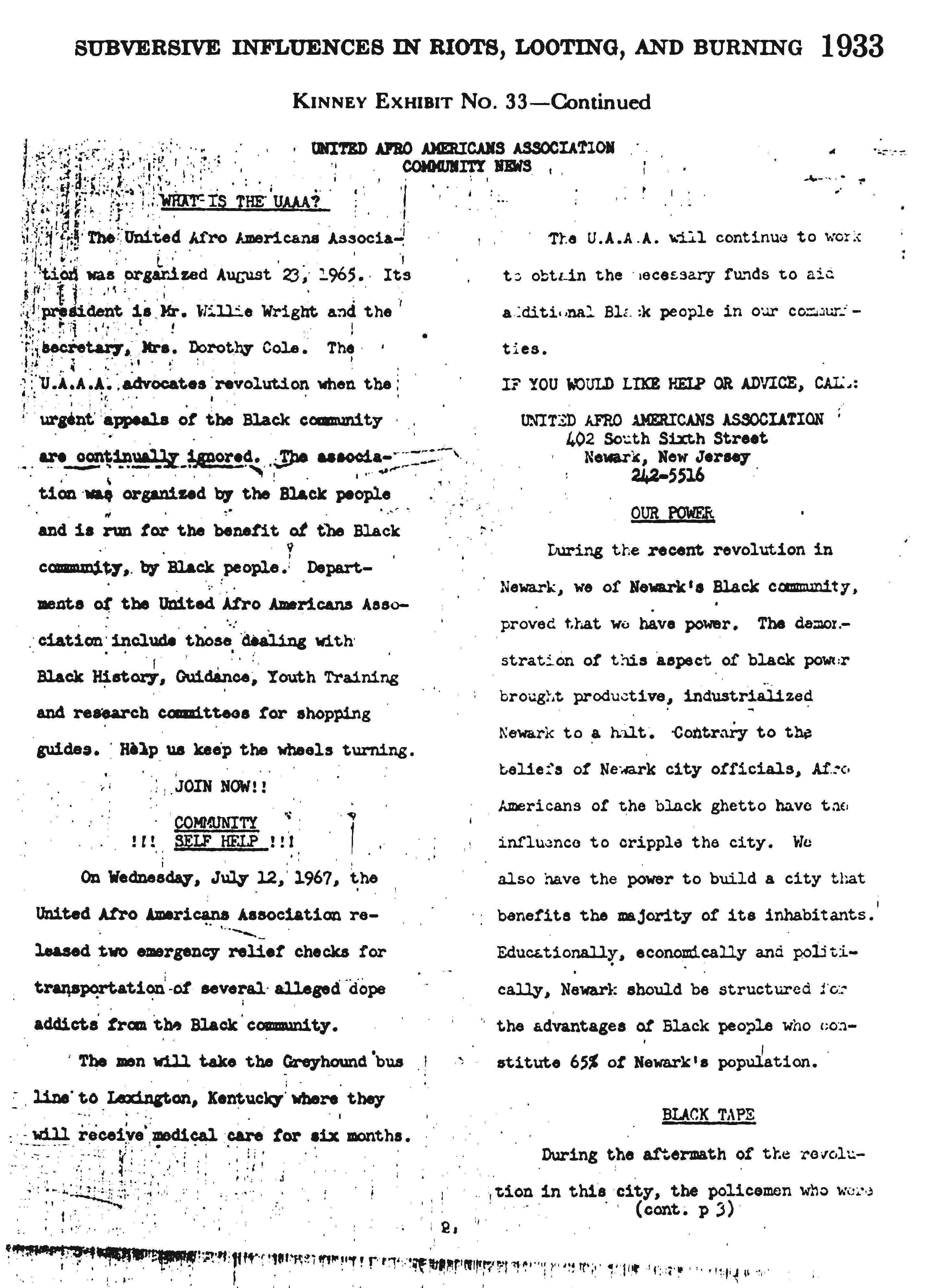

Willie Wright was born May 27, 1928 in Albany, Georgia and worked as a stationary engineer for the Pennsylvania Central Railroad after moving to Newark. A resident of the Central Ward, Wright first lived at 179 Newton Street before later moving up Springfield Avenue to 402 South 6th Street, where he lived in an apartment above the headquarters of his organization, the United Afro-American Association (UAAA). Wright formed the UAAA in 1965, which he envisioned as an organization that “advocates revolution when the urgent appeals of the Black community are continually ignored.” Though a relatively small group, the UAAA came to attract the media spotlight in the late 1960s for the militant rhetoric of its leader.

The same year that Wright established the UAAA, he also got involved with the United Community Corporation (UCC), Newark’s War on Poverty agency which was launched in 1965. The UCC’s structure was designed to empower local people to become leaders in the organization and their communities. Wright was elected as vice president of the UCC’s Board of Trustees, as well as president of Area Board #2 in the Central Ward. As president of Area Board #2, Wright caught the eye of civil rights leaders organizing in other parts of the city. Phil Hutchings, an organizer with the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), said of his first impression of Wright: “he seemed like somebody who was an agitator, and somebody who commanded attention.”

In his public speeches, Wright promoted Black Power and spoke of the need for Newark’s Black communities to develop “community power bases,” and to “control their own area.” “There was nobody who was at all comparable to Malcolm in Newark,” Hutchings said, “but seeing Willie– articulate, dark-skinned, African American, militant rhetoric– in the back of my mind i said, ‘Hey, this could be our local Malcolm X.”

As president of Area Board 2, Wright was a regular figure in the mounting protests for civil rights and political power in the months leading up to the 1967 Newark Rebellion. Wright’s part in “raucous” protests during the Medical School Blight Hearings in May 1967 to prevent the displacement of 20,000 Central Ward residents for a state medical school, shut down one of the hearings, and contributed to the ongoing controversy over the roles of militant Black leaders in the UCC. The following month, he was one of several conference callers of the Newark Organizers Training Institute, alongside Hutchings (SNCC), Bob Curvin (CORE), Tom Hayden (NCUP), Junius Williams (NCUP), Jesse Allen (NCUP), and others, formed to promote “strong grassroots organizations” that summer.

In the wake of the 1967 Newark Rebellion, Wright emerged alongside Amiri Baraka as a figurehead of the city’s more militant, nationalistic leadership that signalled new directions for civil rights organizing in Newark. Though the UAAA had a relatively small following, Wright captured the media spotlight, including the attention of noted Black journalist Louis Lomax, with his fiery rhetoric and claims of thousands of followers. “Our attack is on a system,” Wright said, “Under pressure, our people have destroyed property. It is the others who have devalued human life all along who now resort to the wanton destruction of human life.”

In the months following the rebellion, Wright was at the center of protests against police brutality and a proposed K-9 unit; white vigilante violence in Newark; and other struggles for equal rights. Through these actions, Wright also drew the surveillance of law enforcement agencies, who described him as having “placed himself in the forefront of those seeking violent answers to the City’s and the Nation’s social problems.”

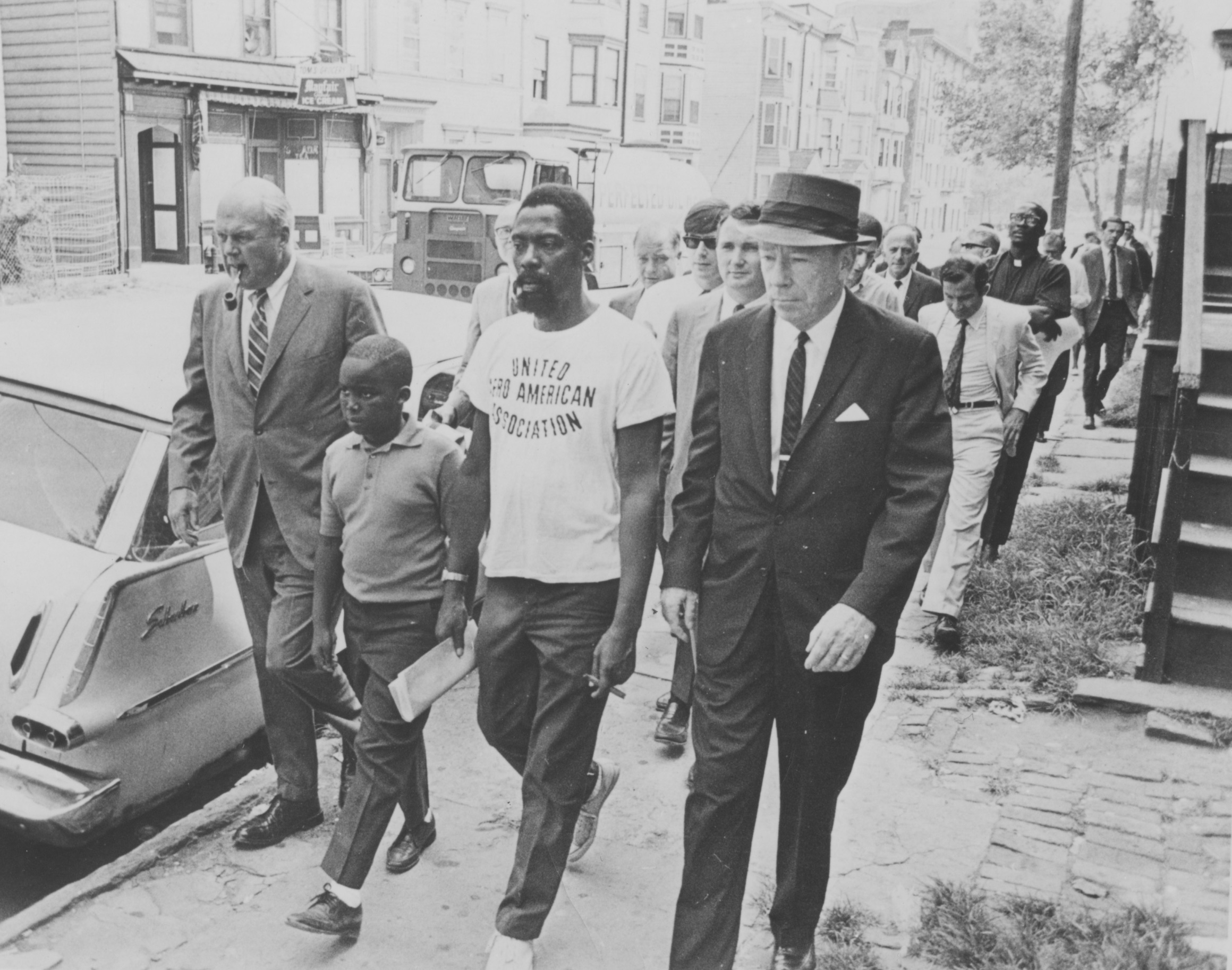

By 1970, Wright began to focus his energies on economic and housing development in the Central Ward. After coordinating a series of walking tours for the Greater Newark Urban Coalition in 1969, which brought business and government leaders through the Central Ward for a “first-hand view” of the problems facing it’s predominantly Black communities, Wright became President of the New Community Corporation (NCC). Led by Msgr. William Linder, the NCC became an influential player in developing housing, retail, and schools for low-income communities in Newark.

References:

Phil Hutchings, interview by Peter Blackmer, January 26, 2017.

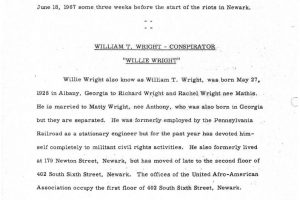

Charles E. Kinney, “Investigation Into Possible Criminal Conspiracy During Riots of July 1967” (Newark Police Department Report)

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Nathan Wright, Jr., Ready to Riot

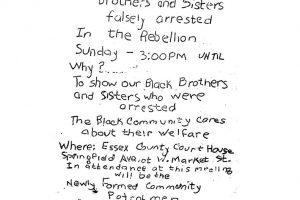

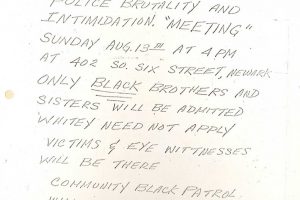

Poster distributed by the United Afro American Association (UAAA) in 1967. Led by Willie Wright, the UAAA was a relatively small organization, but garnered much attention for Wright’s militant rhetoric following the 1967 Newark Rebellion. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

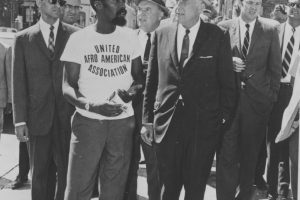

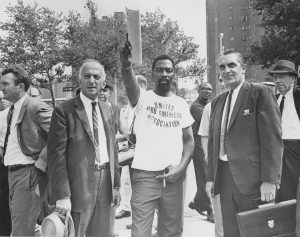

Willie Wright (center) leads a group of Newark businessmen on a tour of the city’s Central Ward in 1968. Wright led tours of the Central Ward to demonstrate conditions in Black neighborhoods and to promote investment in the area. — Credit: Newark Public Library

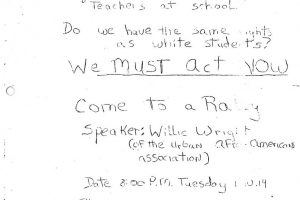

Newsletter distributed by the United Afro American Association (UAAA) in 1967, and used as evidence by Newark Police Captain Charles Kinney as evidence of “criminal conspiracy” during the 1967 Newark Rebellion. — Credit: House Committee on Un-American Activities (1968)

Becky Doggett remembers Willie Wright. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection