Michael Moran

Michael Moran was a captain in the Newark Fire Department and lived at 66 Eastern Parkway with his wife, Ann, and six children. Moran, a 15-year veteran in the fire department, would help out with chores at a charity mission, the Little Sisters of the Poor, on Central Avenue in his off-duty time.

Around 10:00 P.M. Saturday, July 15th, Michael Moran was at Fire House Eleven on Central Avenue when .30 caliber bullets struck the side of the building. Believing that they were under attack from snipers, the firemen inside hit the lights and dropped to the floor.

This gunfire, however, came from a National Guard checkpoint at Central Avenue and 9th Street, where guardsmen were shooting at a car driven by Howard Edwards. On his way from Staten Island to visit a co-worker in Newark, Edwards and his brother were startled by Guardsmen and ran through a blockade. As guardsmen along the avenue responded by firing at the car, shots hit the firehouse and a stray bullet hit a sprinkler pipe inside a factory at 500 Central Avenue. This triggered the factory’s alarm system, which had a direct link to Fire House Eleven down the block.

Minutes later, Michael Moran and his fire company responded to the alarm coming from the factory across Central Avenue from Fire House Eleven. Moran stood at ground level of the building, about a block from the National Guard blockade at South 9th Street, as his men rolled out the hose and raised a 30-foot ladder to the upper floors of the factory.

Newark Fire Director John P. Caufield was outside the building with Moran as firemen hoisted up the ladder. “I stood on one side of the ladder and Capt. Moran on the other…then, the sniper opened fire. We couldn’t see where the bullets were coming from but we knew from the sound that it was automatic weapon fire.”

“I heard Capt. Moran say ‘I’m hit,” Caufield continued. “He slumped down behind the truck. One of the guardsmen was hit, too.”

Moran was hit in the left side by a bullet that had ricocheted off the building wall. According to journalist Ron Porambo, “Moran was facing the building so the shots had to come from the left—from down the street where the string of roadblocks were. It is extremely probable that the guns which had come so close to taking Edwards’ head off were the same weapons responsible for Mike Moran’s death.”

Howard Edwards was widely blamed for shooting Moran, but he was never charged for the crime. Many accounts refute either Edwards or his brother possessing or discharging a firearm.

Moran was rushed to Presbyterian Hospital by Battalion Chief David Kinnear, but succumbed to his injuries on the way there.

Michael Moran was dead at the age of 41 after having been shot while responding to a fire alarm near a National Guard blockade. “A lot of the firemen came up to the hospital when they heard the news,” Fire Director Caufield recalled. “We were all in tears.”

The Essex County Grand Jury found “no cause for indictment” of any alleged snipers or any law enforcement officers involved.

References:

Ronald Porambo, No Cause for Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark

Witness Testimony of Denise Harris before the Essex County Grand Jury

Capt. Michael Moran’s son, Mike Moran, speaks about his father’s death with Karen Yi. — Credit: NJ Advance Media

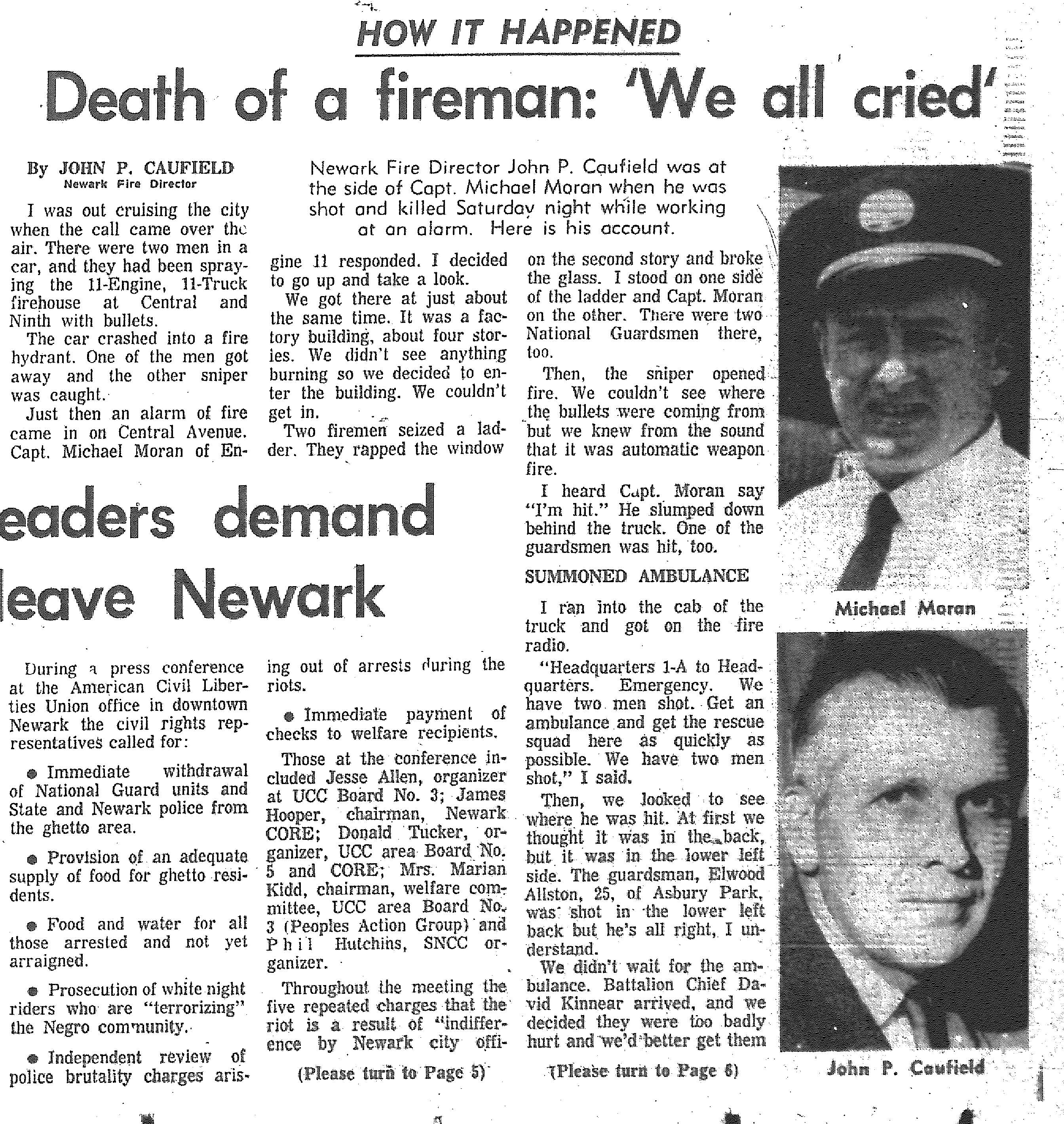

Article from the Star-Ledger on July 16, 1967 covering the shooting of Newark Fire Captain Michael Moran. — Credit: The Star-Ledger

Article from the Star-Ledger on July 17, 1967 covering the shooting of Newark Fire Captain Michael Moran. — Credit: The Star-Ledger

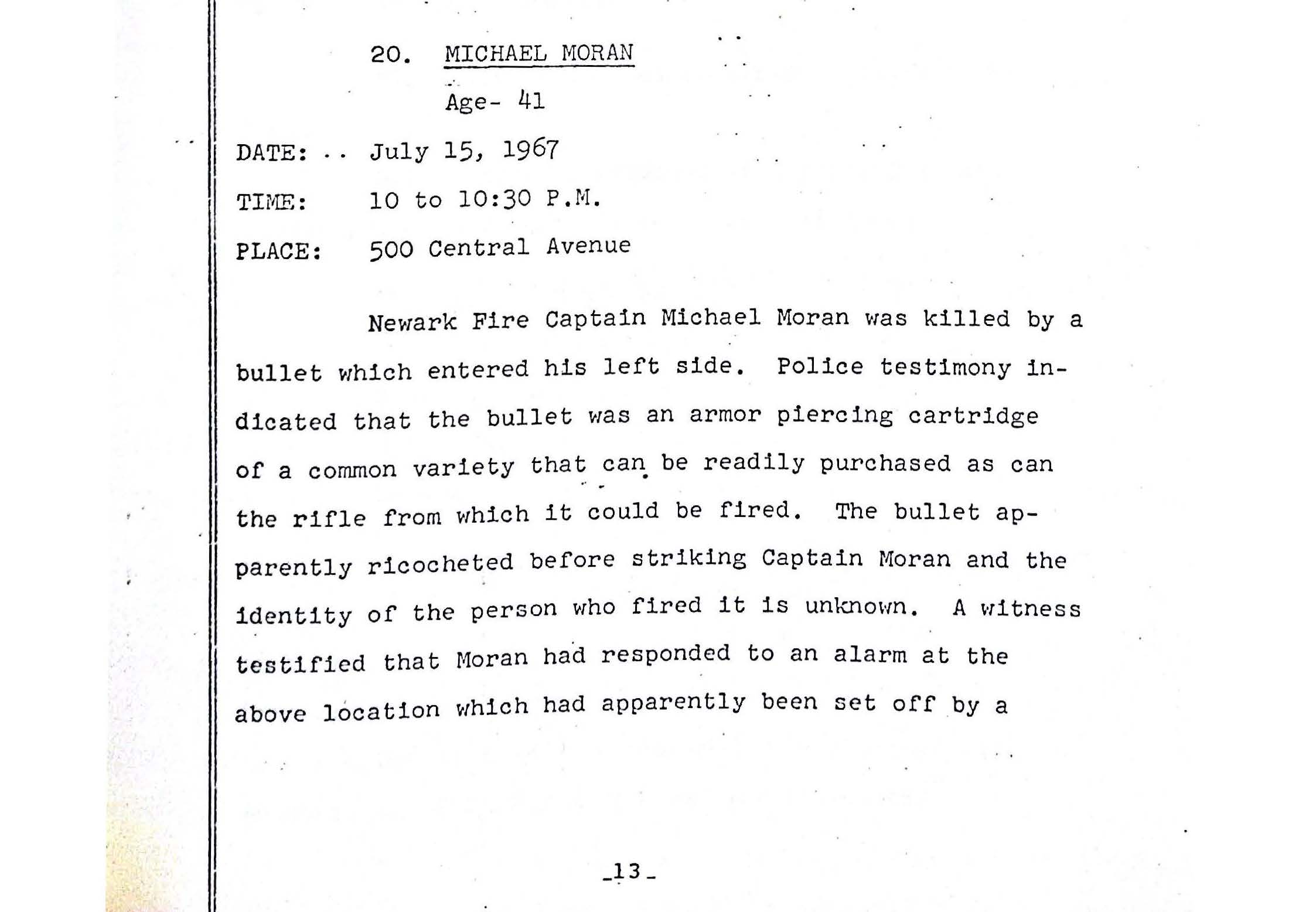

Grand Jury report on the fatal shooting of Michael Moran, on July 15, 1967. The Grand Jury found “no cause for indictment.” — Credit: Newark Public Library