The Mayor

“I think it emulates from individuals in the community who are more concerned about themselves, perhaps, than they are concerned about doing something in relationship to civil rights.” -Mayor Hugh Addonizio

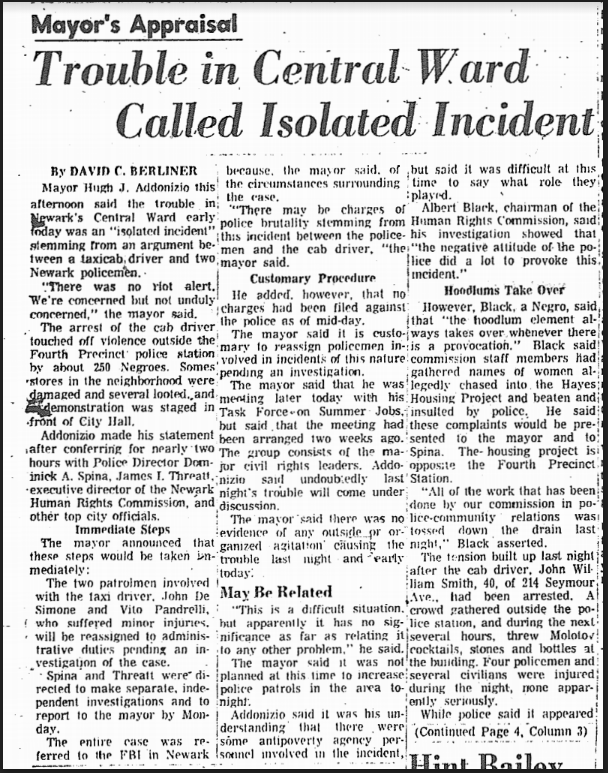

By the accounts of many members Newark’s African American community, the city was ready to explode by July of 1967. Conflicts between the community and city government over the location of a proposed medical school, the appointment of James Callaghan over Wilbur Parker for a board of education position, and continued allegations of police brutality created an increasingly tense atmosphere in Newark. With the level of tension so high, it was little surprise to many city residents when police clashed with protestors outside the Fourth Precinct after the arrest and beating of John Smith on July 12th. As protestors remarked upon the histories of police abuse and official indifference that night, Newark Mayor Hugh Addonizio explained to reporters that the conflict was “an isolated incident” having “no significance as far as relating it to any other problem.” The Mayor went on to announce that the following actions would be taken: the two arresting patrolmen would be reassigned to administrative duties pending an investigation; Police Director Dominick Spina and Newark Human Rights Commission Chairman James Threatt would conduct separate, independent investigations; and the entire case would be referred to the FBI.

The next day, Addonizio went from meeting to meeting with community leaders and organizations to discuss the events of the previous night and how the city government would respond. In a meeting with Robert Curvin (CORE), Jimmy Hooper (CORE), and Police Director Spina, the main topic of conversation was the history of complaints of police brutality brought to City Hall by civil rights organizations. According to Curvin, “the meeting was a disaster” and “there was absolutely no recognition of the nature of the situation that existed in the community.” Addonizio also met with a group consisting of Earl Harris, Harry Wheeler, Eulis “Honey” Ward, and George Richardson. During this meeting, the group suggested a “blue-ribbon commission” to look into what happened Wednesday and report back to the community. According to Harris, the mayor asked for 48 hours to think over the suggestion, to which Harris replied “Mayor, the climate being what it is, I don’t think you have 48 hours before additional harm comes to Newark.” Just hours later, a second round of demonstrations outside the Fourth Precinct turned violent and the city entered its second night of violent unrest.

While Addonizio met with these various groups, the United Community Corporation met to come up with a set of “resolutions to assist in dealing with the present crisis.” Among these suggestions was the promotion of Black police officers to leadership positions, the immediate suspension of the arresting officers of John Smith, and convening a grand jury to investigate allegations against the Police Department. At the end of the day, the only additions to Mayor Addonizio’s initial response was to establish a “blue-ribbon commission” to investigate the cause of violence and looting (to be appointed within 10 days) and to name a Black police officer to the rank of captain. In response to the Mayor’s reluctance to act upon the conflict in a meaningful way, Newark attorney Carl Katidus told Addonizio “The people have lost confidence in this city and this administration. We’re in a state of riot now.”

After violence broke out for the second straight night outside the Fourth Precinct, a “hysterical” Addonizio phoned Governor Richard Hughes insisting that he deploy the National Guard and State Police to the city. Upon the arrival of Hughes and additional law enforcement agencies, Addonizio “almost completely withdrew from any sharing of the direction of this situation,” according to the Governor. The Mayor later said, “During the whole course of this thing I was sort of left out of a lot of things that were going on and this is my city and I have to stay after all the people pull out.” When the state and national presence finally left, it was clear that Newark was no longer Addonizio’s city.

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation.

Ronald Porambo, No Cause for Indictment: An Autopsy of Newark

Witness Testimonies before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders

Clip from an interview with former Deputy Mayor of Newark Paul Reilly, in which he describes the thought process in City Hall when the Newark Rebellion broke out in July, 1967. Reilly discusses the chain of command that was established during the Rebellion, with Governor Richard Hughes assuming almost full control. Reilly served as Deputy Mayor during the administration of Mayor Addonizio, from 1962-1970. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Interview footage with Mayor Addonizio during the 1967 Newark rebellion in which he describes the July events as “partly a civil rights demonstration.” Mayor Addonizio also mentions having clergy wear arm bands to go into communities to promote peace and quell the disorders. –Credit: Sandra King

Clip from interview with Donald Malafronte, aide to Mayor Addonizio, in which he reflects upon a meeting with community leaders on July 13th, the day after taxi driver John Smith was arrested and beaten outside of the Fourth Precinct. Malafronte describes being “chilled” by the demeanor of community leader Robert Curvin during the meeting. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

Article from the Newark Evening News on July 13, 1967, the day after John Smith was arrested and beaten by Newark Police outside of the Fourth Precinct. The article describes Mayor Addonizio’s responses to what he called “an isolated incicdent,” including assigning the police officers involved to administrative duty, ordering investigations, and referring the case to the FBI. — Credit: Newark Evening News

Clip from an interview with former Deputy Mayor of Newark Paul Reilly, in which he describes Mayor Hugh Addonizio’s decision to call for help from Governor Richard Hughes during the 1967 Newark Rebellion. Reilly explains Mayor Addonizio’s feeling that he had “lost his city,” and how the Rebellion dashed his goals for running for Governor of New Jersey. Reilly served as Deputy Mayor during the administration of Mayor Addonizio, from 1962-1970. — Credit: Junius Williams Collection

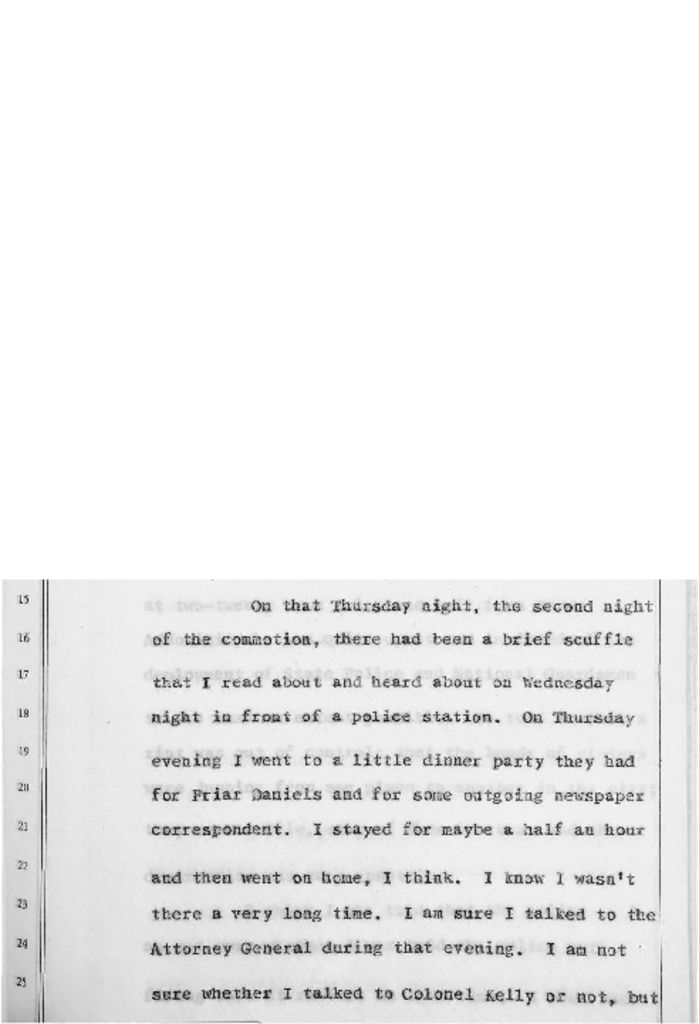

Excerpt from the witness testimony of Governor Richard Hughes before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders on October 2, 1967. In his testimony, Governor Hughes describes receiving a phone call from a “panicked” Mayor Addonizio insisting on the deployment of State Police and National Guard to Newark. Governor Hughes also explains that Mayor Addonizio relinquished leadership during the 1967 Newark rebellion to the Governor. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

Excerpt from the witness testimony of Robert Curvin before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders on October 17, 1967. In his testimony, Curvin describes a meeting at City Hall on Thursday, July 13, 1967 with James Hooper (CORE), Mayor Addonizio, and Police Director Dominick Spina. The meeting, held the day after John Smith was arrested and beaten by Newark Police, was held to discuss government responses to issues of police brutality in the community. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

The Governor

“The line between the jungle and the law might as well be drawn here as any place in America.” -Governor Richard Hughes

New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes had just gotten to sleep the night of Thursday July 13th when he was awoken by a phone call from a “panicked” Hugh Addonizio, the Mayor of Newark. Hughes had spent the night speaking with government officials and police officers regarding the conflict in Newark following the arrest and beating of John Smith the night before. At about 2:20 a.m., Mayor Addonizio called Hughes insisting that the Governor deploy the State Police and National Guard to control the “rioting” going on in the city. For two nights, city police had clashed with protestors as officers responded to heightening protest with increasingly violent force.

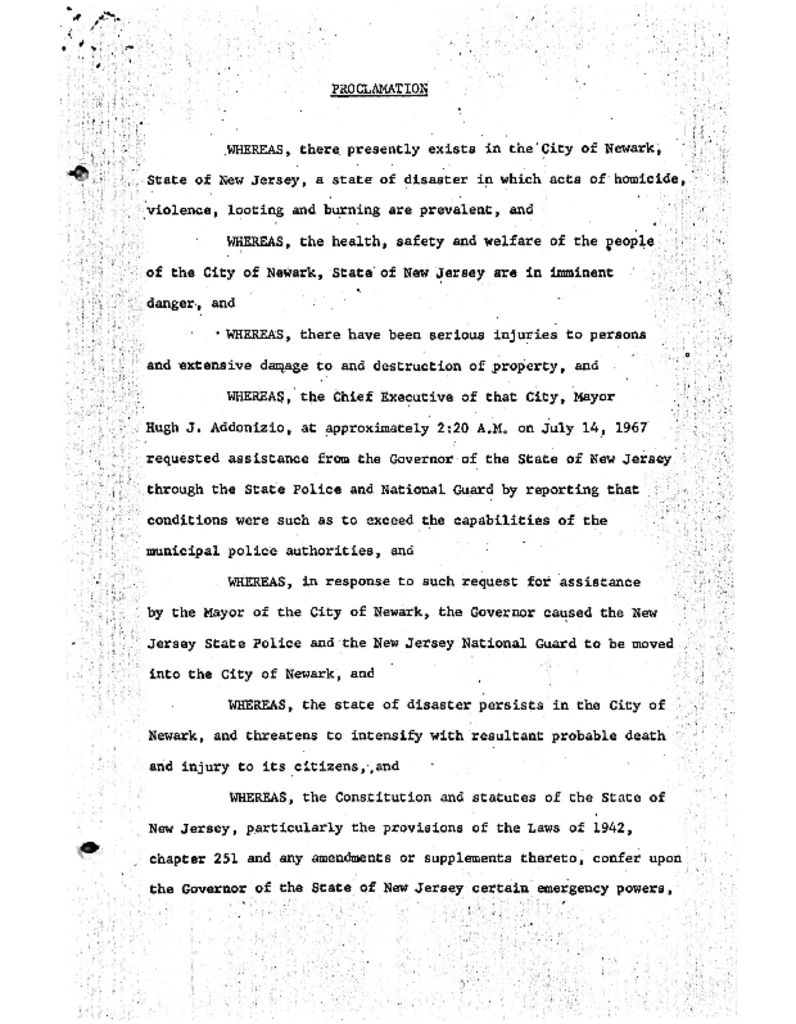

After speaking with Addonizio, Governor Hughes called General James Cantwell of the New Jersey National Guard and Colonel David Kelly of the New Jersey State Police to send the National Guard and State Police into Newark before leaving for the city himself. At 8:30 Friday morning, Hughes toured the “riot area” in the Central Ward with Mayor Addonizio, Police Director Dominick Spina, General Cantwell, Colonel Kelly, and others to assess the situation. Upon touring the area, Governor Hughes described the “riot” as a “criminal insurrection against society, hiding behind the shield of civil rights” and issued proclamations declaring Newark to be in a “state of emergency.” Through these proclamations, Hughes established a curfew, prohibited the sale and possession of alcohol, restricted travel within the city, and directed police and National Guard to “take any and all measures requisite to quell disturbances and outbreaks of violence.” “Any and all measures” would come to include indiscriminately firing at high-rise apartments, vehicles, and pedestrians.

In addition to directing law enforcement agencies during the rebellion, Governor Hughes also met with community leaders to discuss ways of addressing the issues facing African Americans in Newark. In a late night meeting at Oliver Lofton’s (Newark Legal Services Project) house on Friday July 14th, Hughes spoke with Timothy Still (UCC), Don Wendell (UCC), Duke Moore (UCC), George Richardson, Harry Wheeler. The group discussed ways of ending the “riot,” providing food and supplies to residents of the Central Ward affected by the “riots,” and the issues in the community leading up to the rebellion. In response, Governor Hughes contacted grocery stores to have food made available and coordinated a group of “four to five hundred people to go on the streets…and try to stop this rioting.”

On Sunday, July 16, Hughes met with Robert Curvin (CORE) and Tom Hayden (NCUP) to discuss what was happening in the community. Curvin and Hayden related to Hughes the widespread violence and destruction caused by the National Guard and State Police and encouraged their withdrawal. According to Curvin, “The Governor felt that the people in the community wanted the National Guard to be riding up and down the street in their open trucks with their rifles displayed as a show of confidence that order would be restored.” Though hesitant, Governor Hughes gradually withdrew the National Guard and State Police on Monday, July 17th.

References:

Donald Warshaw and James McHugh, “Hughes: ‘A city in open rebellion,” The Star-Ledger, July 15, 1967

Proclamation of Governor Hughes Declaring State of Emergency, July 14, 1967

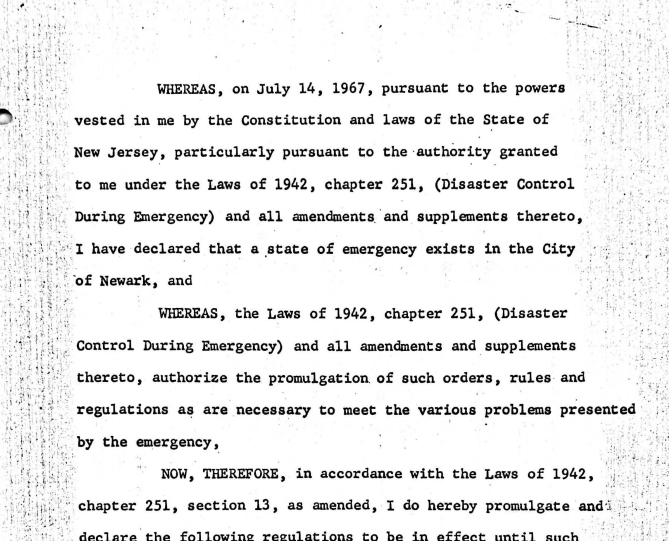

Proclamation of Governor Hughes on Emergency Regulations, July 14, 1967

Witness Testimonies before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders

Clip from “Newark: The Slow Road Back,” in which Governor Richard Hughes recalls his experiences and actions during the 1967 Newark rebellion. The clip also includes interview footage from Hughes during the rebellion stating that “those involved are criminals in my judgement…I think the American people are pretty tired of this cloak of civil rights activity shielding this criminal activity.” –Credit: Sandra King

Proclamation signed by Governor Hughes at 9:34 PM on July 14, 1967 declaring emergency regulations to be in effect in Newark. By declaring a “state of emergency” in Newark, Hughes was able to enforce a curfew, restrict travel in the city, and restrict possession or distribution of alcohol and firearms. The proclamation gave police and National Guard the right to take “all actions necessary to implement and effectuate these regulations.” –Credit: New Jersey State Archives

Explore The Archives

Proclamation signed by Governor Hughes at 9:34 PM on July 14, 1967 declaring that “a state of emergency exists in the City of Newark.” By declaring the “state of emergency,” Hughes invoked “emergency powers,” such as establishing a curfew and restricting traffic within the City. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

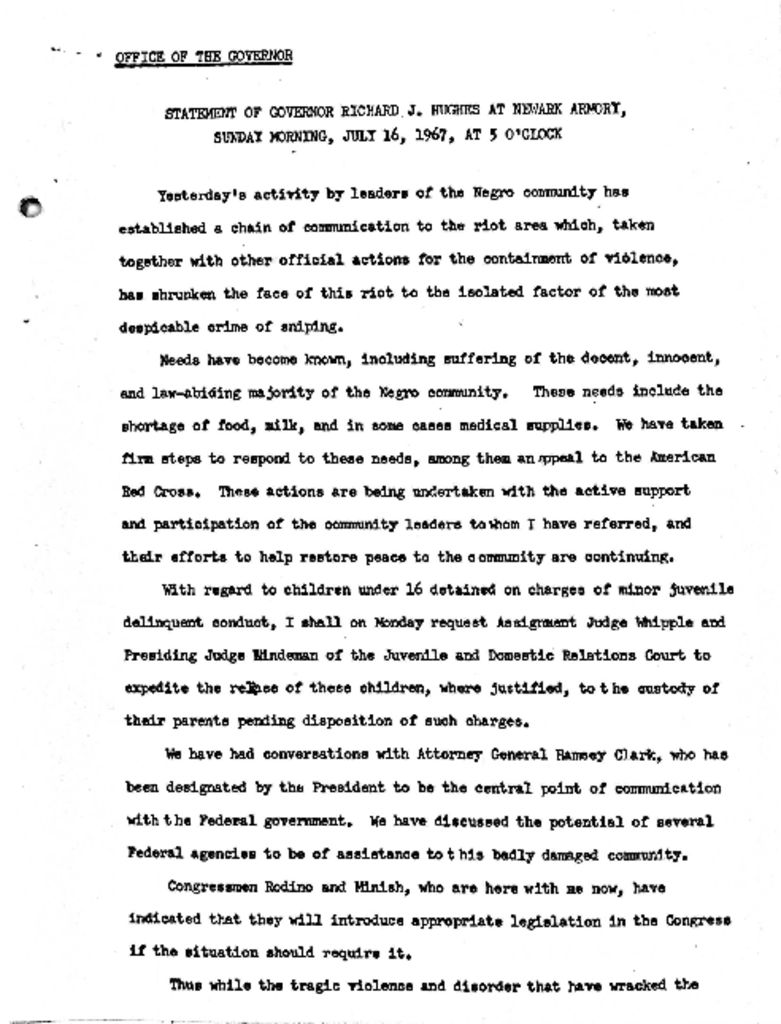

Statement issued by Governor Hughes on the morning of Sunday, July 16 from the Newark Armory. In the statement, Hughes offers executive clemency for anyone arrested during the “riots” who provides information leading to the arrest and conviction of “snipers.” While frequently reported by police and National Guard to justify “indiscriminate shooting” at buildings, vehicles, and individuals, the presence of snipers has been widely discredited by community members, reporters, and historians. No one took Hughes up on his offer. — Credit: New Jersey State Archives

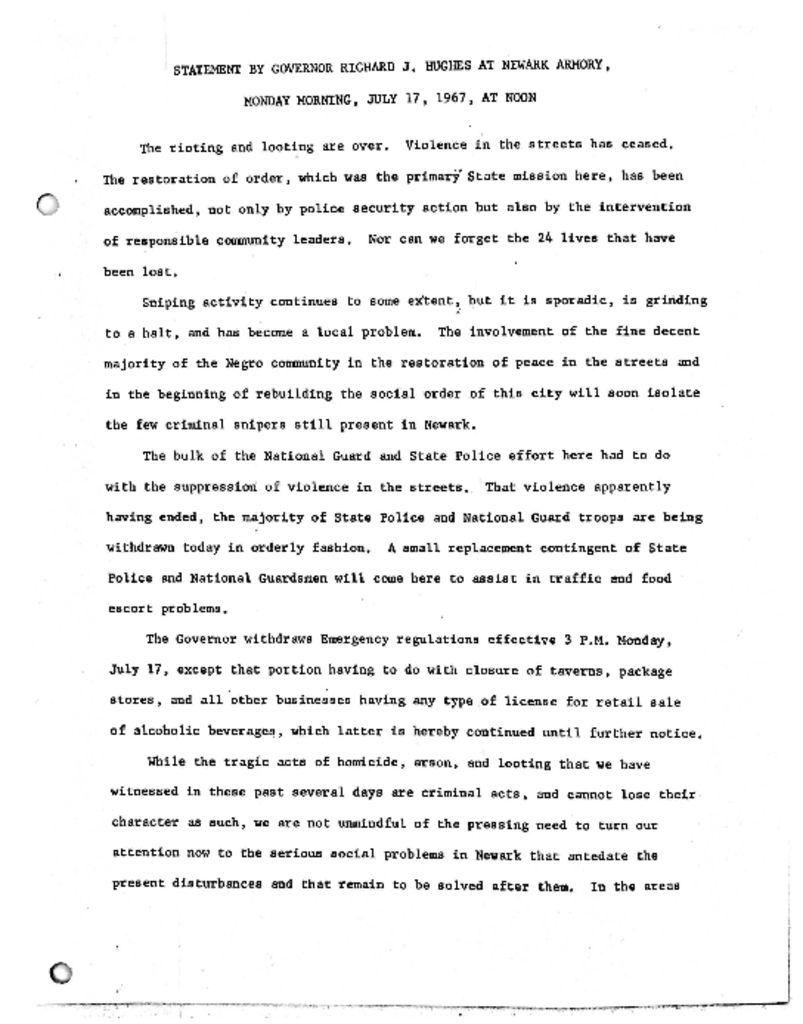

Statement issued by Governor Hughes on Monday, July 17 from the Newark Armory. In his statement, Hughes announced the withdrawl of the majority of State Police and National Guard, as community leaders had been requesting for several days, and pledged support in “attacking the major problem areas” in the City. –Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

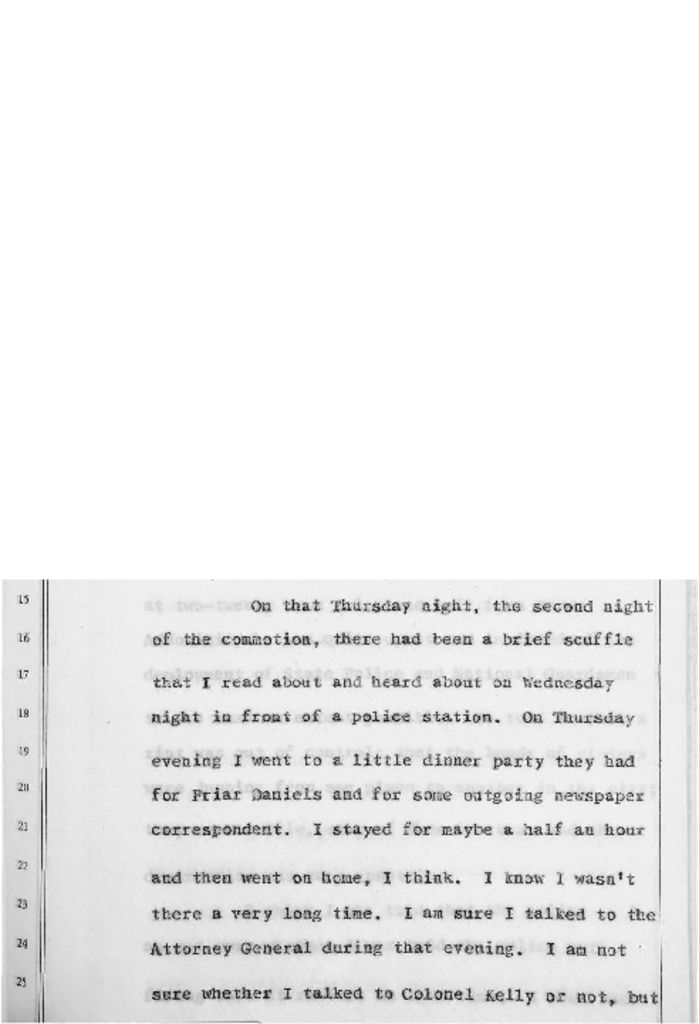

Excerpt from the witness testimony of Governor Richard Hughes before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorders on October 2, 1967. In his testimony, Governor Hughes describes receiving a phone call from a “panicked” Mayor Addonizio insisting on the deployment of State Police and National Guard to Newark. Governor Hughes also explains that Mayor Addonizio relinquished leadership during the 1967 Newark rebellion to the Governor. — Credit: Rutgers University Digital Legal Library Repository

The President

“What’s happening in Newark, New Jersey? Isn’t that hell?” –LBJ to Arthur Goldberg, US Ambassador to the UN

On July 27, 1967 President Lyndon B. Johnson told the nation in a televised address that “we have endured a week such as no nation should live through.” That week, the City of Detroit erupted after police raided a celebration for Black Vietnam veterans at an unlicensed bar in the city’s oldest Black neighborhood. Detroit’s rebellion, which left 32 African Americans dead, came less than a week after police and National Guardsmen in Newark had waged open warfare on the city’s Black populations and businesses. To President Johnson, these rebellions represented a dangerous challenge to “law and order” in the nation’s cities that needed to be dealt with forcefully. They also raised serious questions about the effectiveness and future of his War on Poverty programs, which were designed to alleviate the “conditions which breed despair and breed violence…. ignorance, discrimination, slums, poverty, disease, not enough jobs.”

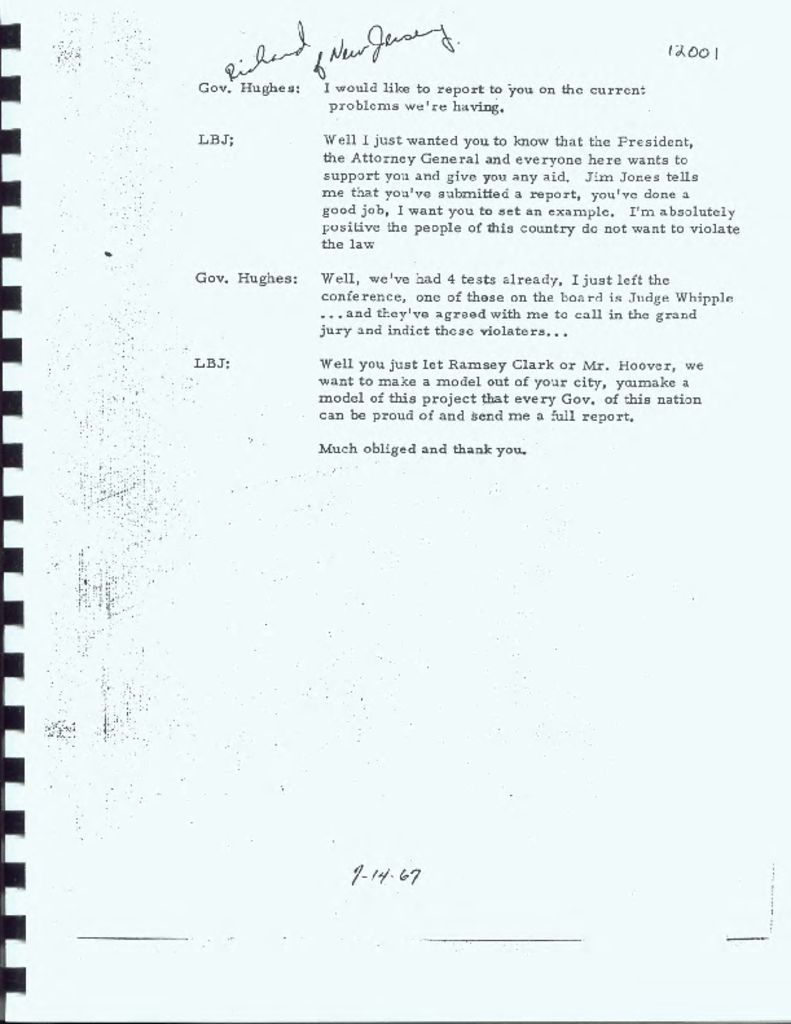

President Johnson’s actions during the Newark rebellion, while minimal, are important to consider. Although President Johnson stated publicly that the federal government would not intervene in Newark, both he and Vice President Hubert Humphrey privately offered federal aid to Governor Hughes in putting down the rebellion. In a phone call from Hughes on Friday July 14, after the National Guard and State Police had already been mobilized in Newark, Johnson told the Governor “everyone here wants to support you and give you any aid.” However, when Vice President Humphrey publicly confirmed the pledge for support, Johnson was “furious.”

There were two main reasons for the President wanting to avoid public involvement. First, conservatives had criticized Johnson for “rewarding” rioters after he supported Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for a large-scale poverty program in Los Angeles in response to the Watts rebellion in 1965. Johnson was also aware that people employed by War on Poverty-funded agencies in Newark were being blamed for inciting the “riot” there. Second, the President did not want to violate the governing powers of the city and state by involving the federal government at the local level. This was a common justification given by Johnson’s predecessors for not intervening in civil rights crises in the South.

In his public responses to the 1967 Newark rebellion, President Johnson both condemned the “lawlessness” of the rebellions and spoke of the continued need for a “genuine, long-range attack” on the conditions that breed “despair” and “violence.” Although Johnson saw the connections between inequality and violence, he did not see “the possibility that the uprisings were a violent expression of civil rights demands, rooted in similar concerns about unequal access and socioeconomic exclusion.” Johnson did not see this possibility because he viewed the “rioting” as the actions of “people that are full of dope and all worked up” or “a bunch of local gangsters” that were incited by black radicals or extremists. Therefore, Johnson took steps to empower local law enforcement, who he saw as “frontline soldiers” in the War on Crime, a lesser-known Johnson initiative to surveil and patrol urban Black communities in response to the “riots” of the 1960s.

In his address to the nation on July 24, 1967 President Johnson stated, “We will not tolerate lawlessness. We will not endure violence. It matters not by whom it is done, or under what slogan or banner…This nation will do whatever it is necessary to do, to suppress and punish those who engage in it.” When we look at the events of the 1967 Newark rebellion, it becomes clear that the greatest acts of “violence” and “lawlessness” were committed by the police and National Guard under the banner of “law and order.” Through Johnson’s rhetoric and policies following the 1967 rebellion, law enforcement agencies were heralded and rewarded, while their victims were further suppressed and punished.

References:

Michael W. Flamm, Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest, and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s

Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America

Julian Zelizer, “A 1965 failure that still haunts America,” CNN January 19, 2015.

Recorded telephone conversation between President Lyndon B. Johnson and Arthur Goldberg, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations at 9:15 AM on July 15, 1967 regarding the Newark rebellion. — Credit: LBJ Presidential Library

Excerpt from President Johnson’s July 24, 1967 address to the nation regarding civil disorder in Detroit and Newark. President Johnson focuses his address mainly upon “law and order” and acts of “violence” and “lawlessness” during the rebellions. — Credit: LBJ Presidential Library

Transcript of a July 14, 1967 telephone conversation between Governor Richard Hughes and President Lyndon Johnson. In the call, Hughes reports to Johnson on the situation in Newark after the outbreak of violence outside the Fourth Precinct the night before. — Credit: LBJ Presidential Library

Explore The Archives

Excerpt from President Johnson’s July 27, 1967 address to the nation regarding civil disorder in Detroit and Newark. After describing his plans for new “riot control” training for the National Guard, Johnson describes in this clip the “long-range solutions” to combatting the “conditions that breed despair and violence.” President Johnson cites many initiatives of his Great Society program as examples of ways the federal government has been working to address urban issues. — Credit: LBJ Presidential Library