Housing

Several different and conflicting housing policies, enacted before the 1960s, created the zone of conflict around housing in Newark:

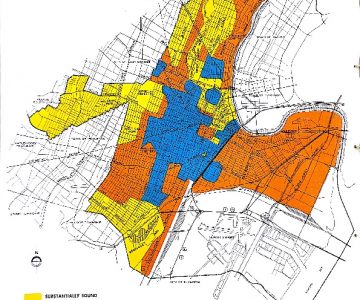

In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was supposed to stimulate housing purchase by offering mortgage insurance for banks to lend, essentially “redlined” all of Newark sending a message to whites that your future was in the suburbs. Simultaneously, their policies denied loans to blacks, keeping them in separate communities and denying African Americans opportunities available to whites. “Redlining” got its name from the practice of lending officers who would draw red lines on maps to mark off neighborhoods that would be denied mortgages or loans.

Privately owned housing in Newark, in neighborhoods where black people were allowed to live, was in many cases substandard and maintained by absentee landlords who had moved to the suburbs. A 1956 issue of Atlantic Monthly magazine described Newark as a “vast scrawl of Negro slums and poverty, a festering center of disease, vice, injustice, crime.” Federally financed Urban Renewal came into these neighborhoods, purchased the property from eager owners, but without a requirement of sufficient housing to replace that which had been demolished. The result was relocation into similar housing or public housing.

Federal dollars invested in Newark produced vast tracts of high and low rise public housing. This housing was at first segregated. But by 1955, according to a study on urban renewal, there were more African Americans than whites in public housing, and the flight of white tenants showed no signs of slackening. By the 1960s, the ratio changed from 77% white to 66% black occupancy in seventeen projects.

In 1964, a group of white organizers from the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chose Newark to began organizing one of their interracial movements of the poor, and housing became its major focus. The organization they formed, the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), was composed of about 12 to 15 organizers, half of them black, living in the area called the Lower Clinton Hill. The other half were white college students, drop-outs or graduates, with two black college students. They organized people based on what the people wanted to see done on their blocks, the intention being to pull the block groups together for collective action from time to time.

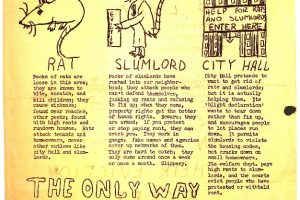

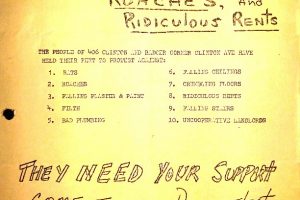

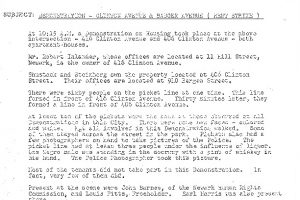

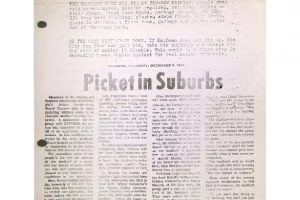

NCUP organizers, black and white, organized rents strikes as well as other targeted protests against storeowners who charged unfair prices, and against police misconduct. Rent strikes were illegal in New Jersey, but at the urging of NCUP tenants withheld their rents to protest high rents and unsafe and unsanitary living conditions maintained by the landlords.

NCUP organizers knew that withholding the money from the landlord would result in the tenant being taken to court, so they arranged lawyers to argue the cases. The rent strikes took the organizers into a realm of neighborhood organizing where people became more empowered by doing things together, taking on more and more issues, and helping one another. At its height, NCUP had approximately 250 members.

NCUP organizers believed blacks and whites could work together to resolve issues like housing, welfare reform, and police accountability. Their integrated project held together until the 1967 Rebellion moved the primacy of race onto front stage.

References:

Kevin Mumford, Newark: A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America

Clip from the film “We Got to Live Here,” in which residents of Clinton Hill describe the condition of housing in their neighborhood and how “slums” are created. — Credit: Robert Machover

Map of “Generalized Environments” in Newark which shows the conditions of buildings in the city in the 1960s. Predominantly white neighborhoods show “substantially sound” housing, while black neighborhoods show “predominantly blighted” conditions. — Credit: Newark Public Library

Clip from the film “Troublemakers” covering the organizing activities of the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP) for better housing conditions in the city. Some of the tactics that NCUP used in housing organizing were: submitting official complaints, petitioning the Newark Human Rights Commission, and organizing rent strikes to force landlords to make repairs. — Credit: Robert Machover