Amiri Baraka and Cultural Nationalism

LeRoi Jones, later to become Amiri Baraka, returned to Newark in 1965. Baraka had spent the previous decade as part of the literary and artistic world of New York City and beyond. One of the best-known and most influential writers of the Black Arts Movement, the cultural and artistic wing of the Black Power Movement, the Black Arts Movement sought to bring Black art to the public through theatrical and literary performances. Jones also took an interest in the emerging network of organizations and leaders theorizing ideas about black liberation through the lens of Black Power. Jones was particularly inspired by the politics and philosophy of the US Organization in Los Angeles, California, headed by Maulana Karenga, which sought to promote African American cultural unity through the politics of cultural nationalism. The creator of Kwanzaa, Karenga, believed that African Americans were a cultural nation in need of a cultural revolution, based on an African paradigm, with the East African trade language Swahilli as a preferred language, and West African customs,drumming, dancing and dress as key features. Karenga would be responsible for changing Jones’ name to Amiri Baraka and shaping his leadership style and values. Upon returning to Newark, Jones played a crucial role in developing the politics of Black cultural nationalism as he helped usher in a new era of Black politics in Newark.

During the 1967 rebellion, Baraka was violently beaten by the police. Appearing bloodied with a large bandage on his head in national media coverage of the uprising, and handcuffed in a wheelchair, he represented the systemic violence and repression at the hands of the police that had sparked the uprising, and its impact on Black people. Already an internationally known writer, his political persona in Newark was heightened by the uprising.

Additionally, the uprising helped to galvanize support for the politics of Black cultural nationalism as mainstream institutions pushed the Black community to embrace more militant stances and to form a parallel set of community-based institutions to meet their own needs. Under Baraka’s leadership in Newark, he and his followers formed the Committee for a United NewArk (CFUN) and the African Free School, which was a community liberation school headed by his wife, Amina Baraka.

Only a few days after the end of the rebellion in July 1967, Newark played host to a Black Power Conference, the first in a series of Black conventions in Newark and part of a broader national convention movement. For Baraka, the convention served as a means to build Black political consciousness and a stepping stone for his own concept of “nation-building.” While Newark was still reeling from the violence of the uprising, the attendants of the convention, which included Rev. Jesse Jackson, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., Maulana Karenga, Robert F. Williams, Phil Hutchings, and H. Rap Brown, debated whether reform or revolution should mark the path ahead.

Baraka’s cultural nationalism was not embraced by all of Newark’s Black leaders. While he was in New York and California, the city’s leadership had established a firm foundation and militant stand against the city’s entrenched white political establishment, through such confrontations as the Parker-Callaghan and Medical School fights. This made it more difficult as Baraka worked to form a united front of Black leaders and organizations to elect black politicians. However, Baraka was able to call together several of the prominent black leaders because of his national status, and new-found celebrity in having been attacked by the police, calling it the United Brothers. The United Brothers brought together Black leaders from across the city and aimed to use their collective power and resources to change electoral politics in Newark. The United Brothers later transformed into CFUN as the organization shifted under Baraka’s influence from focus on the election of Newark’s first Black mayor to embracing a more encompassing form of cultural nationalism.

Baraka’s call for a “black united front” was informed by his brand of Black cultural nationalism, which emphasized the need for Black self-determination and political as well as cultural revolution. Believing Black culture marked the black community as a nation within a nation, Baraka saw electoral politics as a critical element of the politics of cultural nationalism. He believed it would enable Black self-determination, including the election of the first Black mayor of Newark, and city council as well.

Seeking to create a slate of “community choice” candidates, the 1969 Black and Puerto Rican Political Convention, chaired by Robert Curvin, brought together an even broader set of leaders. Nevertheless, through his national fundraising for what he called the NewArk Fund and the strong community presence through his organized group of vocal and disciplined followers, Baraka and his followers remained a prominent and not too subtle feature of the convention. As expected, Kenneth Gibson emerged from the 1969 convention as the “community choice” candidate for mayor, along with candidates for all nine council seats. Baraka put the force of his organizations and resources behind his campaign, although Gibson, a moderate, did not embrace the politics of cultural nationalism. Nevertheless, Baraka and CFUN played a key role in Gibson’s campaign. Drawing college students from across the tri-state area, Baraka put them to use knocking on doors and registering voters. Additionally, he used this celebrity to attract other notable African Americans to come to Newark to campaign for Gibson, including Jesse Jackson, Harry Belafonte, and Stevie Wonder.

The relationship between Baraka and Gibson began to deteriorate shortly after his election. While Baraka believed in the platform formulated during the convention, including the calls for a police review board, Gibson instead took a more conservative approach to governing the city-even, saying that he was the police review board. Additionally, Gibson did not give Baraka the jobs his followers needed. Baraka’s Kawaida Towers project further strained their relationship, a low-to-moderate housing project he hoped to build in Newark’s North Ward, a historically Italian-American community. In the fight, marked by racism and white backlash that ensued over the project, Gibson failed to put his full political support behind Baraka-a decision that marked the end of their tenuous alliance.

As Gibson ran for reelection in 1974, Baraka and CFUN held another political convention and generated a complete slate of city council candidates. However, none of these candidates, including the incumbent councilman for the Central Ward, Dennis Westbrooks, won a seat on the council as part of the Community Choice slate. Thus in 1974, while Newark had both a Black mayor and a Black city council president, Earl Harris, whose political careers had been propelled by CFUN, Baraka’s vision of Newark serving as the first of a series of cities where cultural nationalism paved the way for Black political power and radical changes in the day-to-day lives of urban Black communities had failed.

Gibson, like other black politicians, benefitted from the politics of black cultural nationalism, but their embrace of the ideology was uneven. A political moderate, Gibson saw the principles of Black cultural nationalism as a barrier to winning white votes and support, and he was generally more interested in minor reforms than revolutionary change as promoted by the cultural nationalism. Consequently, while proponents of Black cultural nationalism had helped to get him elected, Gibson would play a role in the downfall of CFUN by his refusal to support Amiri Baraka during the battle over Kawaida Towers. This perpetuated Baraka’s retreat from nationalism of any sort, and his reemergence as a cultural icon who celebrated his embrace of Marxism.

References:

Amiri Baraka, The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Komozi Woodard, A Nation Within A Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics

Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) explains the importance of art for promoting self-consciousness, empowerment, and liberation. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A spoken word performance by children from Amiri Baraka’s Spirit House Movers and Players in Bedford-Stuyvesant, 1968. –Credit: PBS Thirteen

Black Power Manifesto and Resolutions

View PhotoA report submitted by the Continutations Committee of the National Conference on Black Power titled “Black Power Manifesto and Resolutions.” The manifesto and resolutions were based on conversations and workshops at the conference held in Newark from July 20-23, 1967. –Credit: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Amiri Baraka describes cultural nationalism in Newark and the emergence of the Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN) and the Congress of Afrikan People (CAP). –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

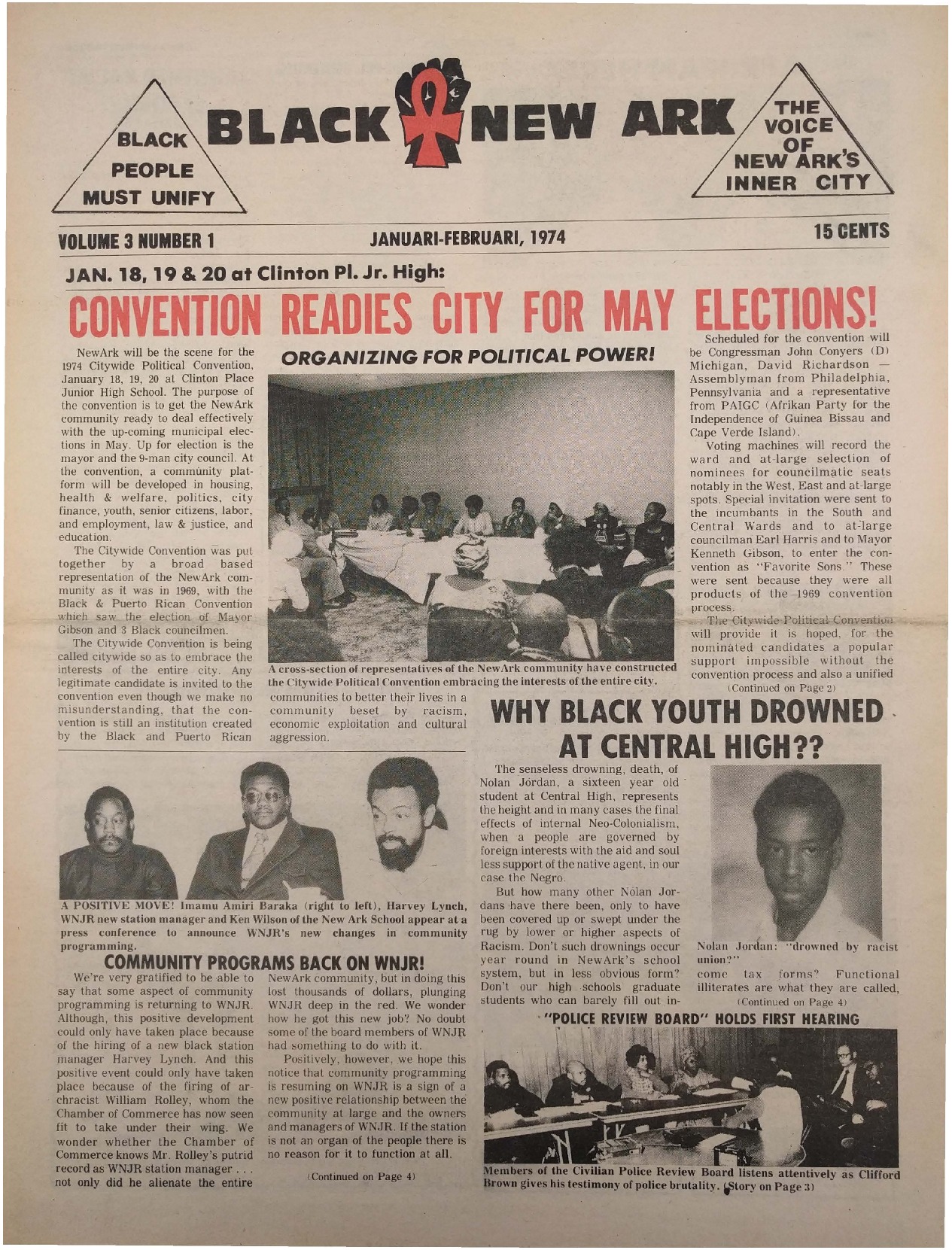

Black NewArk (Jan-Feb 1974)

View DocumentVolume 3, Number 1 of the CFUN newspaper, Black NewArk, published in January-February 1974. This edition of the paper includes coverage of the 1974 Citywide Political Convention. — Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

Congress of African People Booklet

View DocumentPromotional booklet for the Congress of Afrikan People, Black nationalist group led by Amiri Baraka. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Amina Baraka and Estelle David describe how their relationship with Ken Gibson changed once he was elected. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Komozi Woodard describes the decline of CFUN following the the unsuccessful struggle to build Kawaida Towers. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection

Explore The Archives

Baraka's Impression of US Organization

Oral interview with Amina Baraka

Outcomes of 1974 Election

Amiri Baraka and Ken Gibson

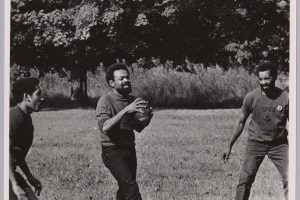

Amiri Baraka Playing Football with CFUN Members

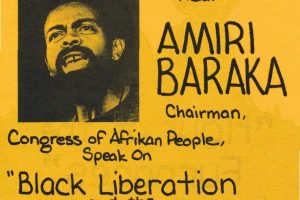

Amiri Baraka Address CAP Conference (1972)

Amiri Baraka Discusses the Formation of the Congress of Afrikan People

Amiri Baraka Interview (1972)

Estelle David Discusses the Role of Women in the Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN)

Baraka Explains the Rebellion

Amiri Baraka Discusses Black Power Conference

Larry Hamm Describes His First Encounter with Amiri Baraka

Kwanzaa Celebration Inside the Hekalu, 3

Kwanzaa Celebration Inside the Hekalu, 4

Kwanzaa Celebration Inside the Hekalu, 5

Gathering at the Hekalu

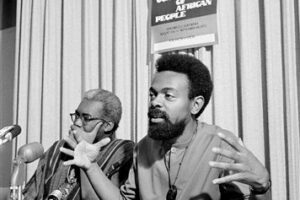

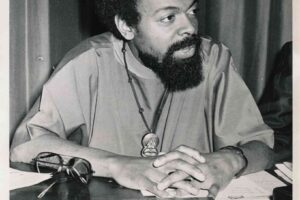

Amiri Baraka at Press Conference (1971)

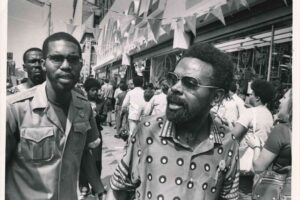

Amirir Baraka on Picket Line (1974)

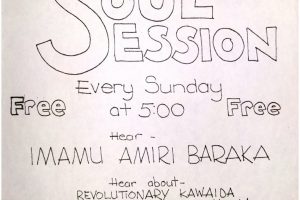

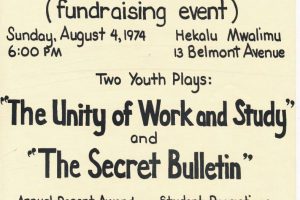

Soul Session Flyer (1974)

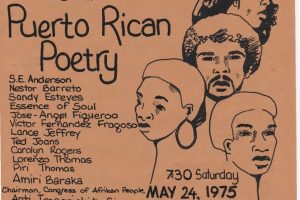

CAP Flyer for Black and Puerto Rican Poetry Event (1975)

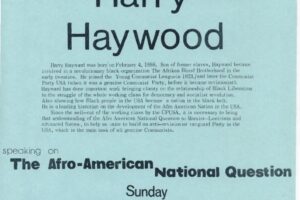

CAP Flyer for Harry Haywood Event (1976)

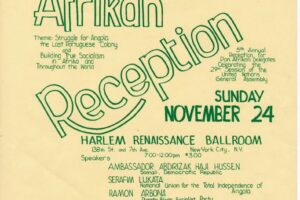

CAP Flyer for Pan Afrikan Reception in Harlem

Flyer for Film Showing at Hekalu (1974)

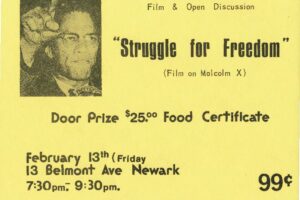

Flyer for Malcolm X Film Discussion at Hekalu (1976)

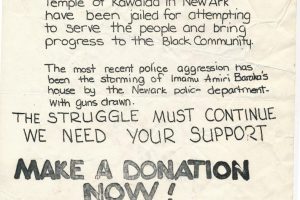

Flyer to Support Kawaida Bail Fund (1974)

Mwanamke Mwananchi (The Nationalist Woman) by Mumininas of CFUN

CFUN Newsletter- Words from Imamu

Committee For Unified Newark Pamphlet (1972)

Strategy and Tactics of a Pan African Nationalist Party (1972)

"Ujamaa, Small Business, Socialism, and Capitalism" (CFUN Newsletter)

"Kawaida Customs and Concepts" (CFUN Newsletter)

CFUN Pamphlet on Marcus Garvey

CFUN Pamphlet on Marcus Garvey

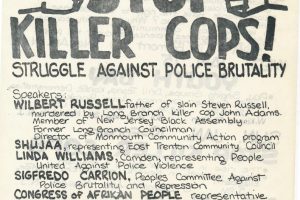

CAP Flyer for Stop Killer Cops Forum (1975)

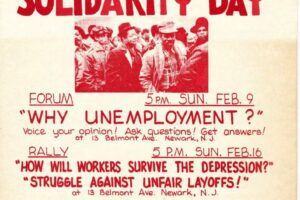

CAP Flyer for Worker's Solidarity Day (1975)

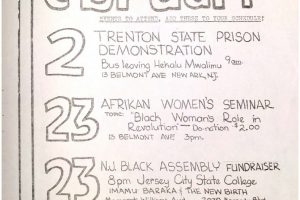

CFUN Flyer for February 1974 Events

Flyer for Afrikan Free School Awards (1974)

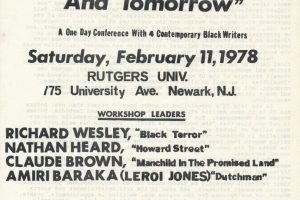

Flyer for Black Writer's Conference (1978)

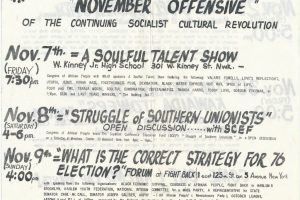

CAP Flyer for November 1975 Events

Flyer for Film Showing at Hekalu (1974)

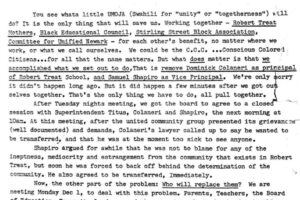

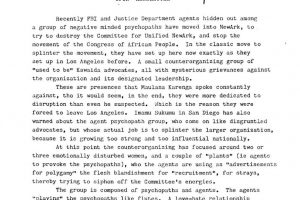

CFUN Newsletter (On FBI Surveillance)

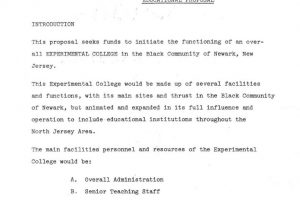

CFUN Proposal for Experimental College

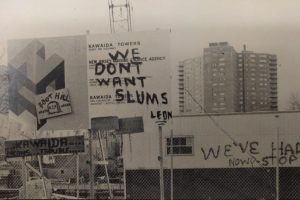

Kawaida Towers

In the early 1970s, after having helped Mayor Kenneth Gibson to become the first black mayor of Newark and established several successful community programs and organizations, Amiri Baraka turned his gaze to large-scale community development with the goal of transforming the Central Ward into a “New Ark.” Leveraging the transformation of the Committee for a United NewArk (CFUN) into the Newark branch of the national organization, the Congress of African People (CAP), Baraka shifted its organizational focus to social transformation through the development of community housing, cooperative businesses, and a host of neighborhood institutions. The first target for Baraka’s urban development plan was a tract of urban renewal land in the Central Ward known as NJR-32. To Baraka and CFUN, their plan for NJR-32 was “a black nationalist alternative to the white supremacist policy of urban renewal.”

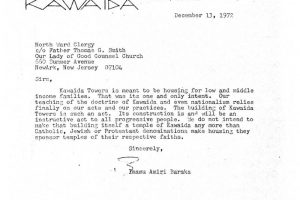

While NJR-32 was delayed by the Newark Housing Authority, CFUN and its allies found a different plot of land to develop housing on in the meantime. In 1972, Amiri Baraka unveiled plans to build housing for low- and moderate-income residents at the corner of Lincoln Avenue and Delevan Street in the North Ward. On the land in this predominantly Italian American neighborhood, CFUN planned to develop a $6.5 million, 16-floor building with over 200 apartment units, along with a theatre, hobby shop, and other community resources for residents. The name of the project, Kawaida Towers, was derived from the cultural nationalist doctrine of Kawaida, meaning “tradition and reason.” Baraka assembled an impressive interracial team of architects, lawyers, and contractors and broke ground on the project in July 1972.

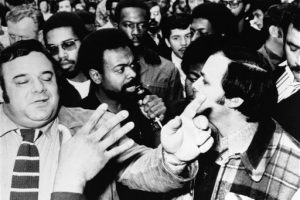

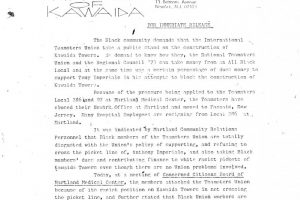

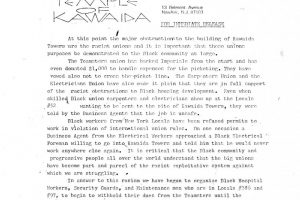

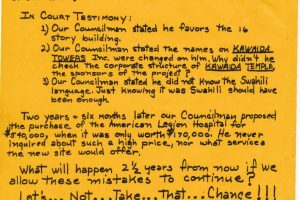

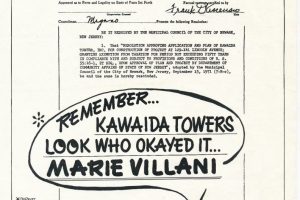

However, it soon became clear that Kawaida Towers would not be built without a fight from white residents of the North Ward. Though the project had been granted tax abatement by the city council with initial cooperation from North Ward City Councilman Frank Megaro, and initially gained the support of Councilman-at-Large Ralph Villani and State Senator Anthony Imperiale, pickets and protests at the construction site began just days after the ceremonial groundbreaking in October 1972.

The cause of the sudden emergence of white backlash was North Ward Democratic Party Chairman Steve Adubato, who had used the ceremonial groundbreaking as a platform to publicly oppose the project. With Adubato, a political power broker in the city publicly challenging the project, the battle lines were drawn. Anthony Imperiale shifted sides and seized the opportunity to lead a public assault against Kawaida Towers by mobilizing members of his North Ward Citizens Committee, along with the Newark Police Department, to hold daily protests at the construction site. Imperiale’s protests quickly swelled as hundreds of white protestors joined in the fray, threatening that “blood would run in the streets.”

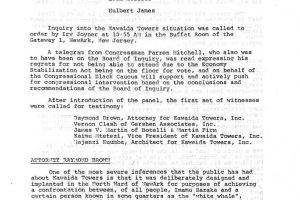

While the crowds of white protestors, aided by Newark police, blocked construction workers from getting to the site, Imperiale and fellow North Ward resident John Cervase filed a lawsuit against the development. In court, the two obstructionists “fabricated technical objections” to the height of the building and the legality of the tax abatement to “disguise their racial objection,” historian and CFUN member Komozi Woodard wrote. Though soundly defeated in court by the legal defense of Kawaida Towers, featuring renowned Attorney Ray Brown, the opposition was taken up by the City Council, who voted to rescind the tax abatement in November 1972. Empowered by the City Council vote, the mobs at the construction site escalated their violence, continuing to block construction workers from entering the site, shouting racial slurs, and attacking black laborers as they tried to get to work.

Though supported by an array of religious, labor, and political organizations, Baraka and CFUN struggled to compete with the numbers and force that Imperiale and Adubato had mobilized in the North Ward in opposition to the project. Furthermore, Mayor Ken Gibson chose mainly to stay on the sidelines of the turmoil and had little or no control over the police department that was playing a central role in the conflict. Police Director John Redden resigned during the conflict, blaming Baraka for fomenting the racially charged opposition to the housing project. Gibson appointed the first black Police Director who was unable to control the police officers as well. Violence spread from the construction site, as white mobs attacked black people in the North Ward. Black students were attacked in school, and shotgun blasts were fired into CFUN headquarters at 502 High Street.

The violent opposition to Kawaida Towers proved insurmountable for Baraka and CFUN. Despite Mayor Gibson and City Councilman Earl Harris both having benefited from Baraka’s support in the 1970 election, both failed to support Baraka and further enabled the opposition to the project. Illustrating the dismay of supporters of Kawaida Towers, CFUN member Saidi Nguvu said, “we had followed the law, and everything was right, but they refused to build it, and they physically attacked us.”

By 1974, Kawaida Towers had been defeated, and in the following year, so too were the plans for NJR-32. With these crushing defeats, the conceptualization of Black cultural nationalism as a means to achieve Black Power as conceived by Baraka, CFUN, and CAP received a deathblow. In the following months, the funding for Kawaida Towers, NJR-32, and the African Free School was withdrawn, and the programs were dissolved. The Newark Housing Authority demolished the buildings that housed CFUN’s theatre and television studio training program, the headquarters of the National Black Assembly, the African Liberation Support Committee, and the classrooms of the African Free School. In 1976, the $1.5 million foundation of Kawaida Towers was buried by the New Jersey Housing Finance Agency.

“The housing development would have institutionalized Baraka at another level in the pantheon of political power,” Junius Williams later reflected. “Along with the other social and educational programs he had designed and implemented, he would have become a formidable force in Newark at yet another level of power—he would have transferred from People Power to power based on position and money.”

References:

Robert Curvin, Inside Newark: Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation

Junius Williams, Unfinished Agenda: Urban Politics in the Era of Black Power

Komozi Woodard, A Nation Within A Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics

Amiri Baraka discusses the fight over the construction of Kawaida Towers, a multi-family housing project he planned to build in the North Ward, in a 2009 oral history with Robert Curvin. — Credit: The Estate of Robert Curvin

Kawaida Towers Rendering (1972)

View DocumentArtist rendering of the Kawaida Towers apartment building, 1972. –Credit: The Star-Ledger

North Ward Residents Block Construction Site (1972)

View DocumentA mob of North Ward residents attempt to block the entrance of the Kawaida Towers construction site, while Oscar Mersier (center) and other Black laborers try to enter with a police escort on November 22, 1972. —Credit: Dwight J. Johnson/The Star-Ledger

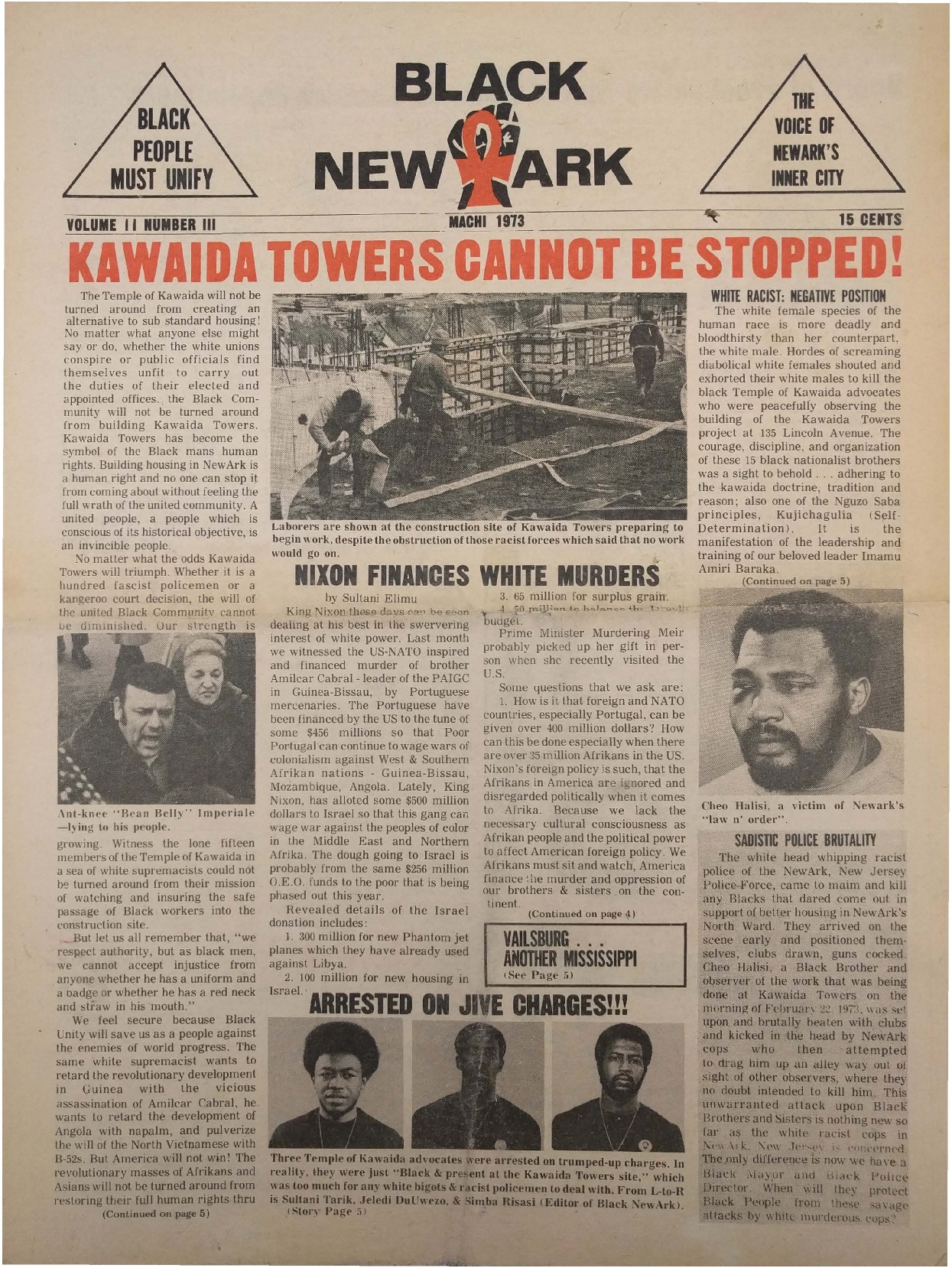

Black New Ark (March 1973)

View DocumentVolume 2, Number 3 of Black NewArk, the local newspaper of the Committee For Unified Newark (CFUN), published in March 1973. The monthly newspaper provided continuous coverage of the fight over Kawaida Towers. — Credit: NYU Tamiment Library

Clip from an interview with North Ward vigilante and politician Anthony Imperiale, in which he discusses his opposition to the construction of Kawaida Towers. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Komozi Woodard reflects on the struggle over Kawaida Towers and its impact on Baraka and CFUN. –Credit: Junius Williams Collection